The Dongria Kondh of India’s Niyamgiri Hills have fought a heroic battle against mining giant Vedanta Resources to save their sacred mountain.

The Supreme Court has told Vedanta that the Dongria must decide whether to allow mining or not. Will the Dongria be allowed to make their decision in peace, and will the government, and Vedanta, respect that decision?

Now their lands and lives are under threat again. Their leaders are being harassed by police and imprisoned under false charges. The Dongria feel the government is trying to destroy their community in order to allow mining.

Royal descendants of the mountain God

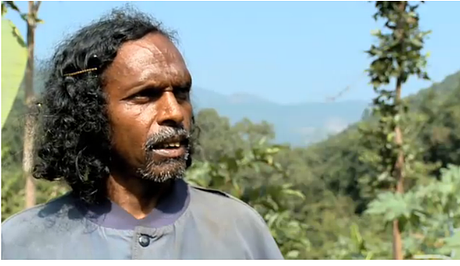

The Niyamgiri hill range in Odisha state, eastern India, is home to the Dongria Kondh tribe. Niyamgiri is an area of densely forested hills, deep gorges and cascading streams. To be a Dongria Kondh is to farm the hills’ fertile slopes, harvest their produce, and worship the mountain god Niyam Raja and the hills he presides over, including the 4,000 metre Mountain of the Law, Niyam Dongar.Yet for a decade, the 8,000-plus Dongria Kondh lived under the threat of mining by Vedanta Resources, which hoped to extract the estimated $2billion-worth of bauxite that lies under the surface of the hills.

The company planned to create an open-cast mine that would have violated Niyam Dongar, disrupted its rivers and spelt the end of the Dongria Kondh as a distinct people.

‘Niyam Raja is our god and we worship him’

The deep reverence that the Dongria have for their gods, hills and streams pervades every aspect of their lives. Even their art reflects the mountains, in the triangular designs found on village shrines to the many gods of the village, farm and forests and their leader, Niyam Raja. They derive their name from dongar, meaning ‘hill’ and the name for themselves is Jharnia: protector of streams.

Living like kings

The Dongria live in villages scattered throughout the hills. They believe that their right to cultivate Niyamgiri’s slopes has been conferred on them by Niyam Raja, and that they are his royal descendants. They have expert knowledge of their forests and the plants and wildlife they hold. From the forests they gather wild foods such as wild mango, pineapple, jackfruit, and honey. Rare medicinal herbs are also found in abundance, which the Dongria use to treat a range of ailments including arthritis, dysentery, bone fractures, malaria and snake bites.

© Jason Taylor/Survival

© Jason Taylor/SurvivalStrangely, mining company Vedanta says that this is ‘virgin land; no human interference has taken place’.

© Jason Taylor/Survival

© Jason Taylor/SurvivalSacrifices and ceremonies

Sacrifices are traditionally made after the harvest and before the planting of the new year’s crop, both in the villages and on the mountain tops. Each village has specific sites for sacrifices and worship of the mother goddess Dharni, Niyam Raja, and other gods of the hills. Each house also has sacred spaces for worship of the many domestic and local gods. Chickens, goats, pigs and – especially – buffalo are sacrificed. The Dongria Kondh have no over-arching political or religious leader; clans and villages have their own leaders and individuals with specific ceremonial functions, including the beju and bejuni, male and female priests. The Dongria believe that animals, plants, mountains and other specific sites and streams have a life-force or soul, jela, which comes from the mother goddess.

Protectors of life-giving streams

© Roberto Caccuri/Contrasto

© Roberto Caccuri/ContrastoThe mining threat

© Survival

© Survival © Jason Taylor/Survival

© Jason Taylor/Survival‘Where will us children go? How will we survive? No, we won’t give up our mountain!’

The illegal refinery

Health

Kondh villagers blame pollution from the refinery for skin problems, livestock diseases and crop damage. ‘Red mud’, a toxic slurry that is the refinery’s main waste product, dries to a fine dust in the sun. Government pollution inspectors have described ‘ground water contamination’ caused by ‘alarming’ and ‘continuous’ seepage of the red mud. The toxic waste has also leaked into the Vamsadhara river.

Environmental damage

© Survival

© SurvivalResistance

The Dongria protested against Vedanta locally, nationally and internationally. They held roadblocks, formed a human chain around the Mountain of Law and even set a Vedanta jeep alight when it was driven onto the mountain’s sacred plateau. But as long as the refinery sits at the foot of their hills, they do not feel their mountain is safe and will not give up their fight. Their determination, tenacity and success has won them international acclaim and inspired tribal peoples across the country and around the world. © Survival

© Survival © Survival

© SurvivalLobbying and support from Survival

Survival has been supporting the Dongria and has lobbied the Indian government, as well as the UK, for the mine to be stopped. We have submitted detailed reports to the UN and the OECD. We have provided the Dongria with legal advice, and our researchers have spent many days talking to them in their communities (as well as being threatened and assaulted by pro-Vedanta ‘goons’). Our film ‘Mine’, on the Dongria’s struggle, has gone viral online. Our lobbying has led several important shareholders, including the Norwegian government and the Church of England, to disinvest from the company. The Church of England said, ‘We are not satisfied that Vedanta has shown, or is likely in future to show, the level of respect for human rights and local communities that we expect’. The UK government ruled that Vedanta ‘did not respect the rights of the Dongria Kondh,’ and ‘did not consider the impact of the construction of the mine on the [tribe’s] rights’. Their investigation concluded that ‘a change in the company’s behaviour’ was ‘essential’. © Survival

© Survival

© Survival

© Survival © John Swannell

© John SwannellCelebrity support

Survival has recruited celebrity supporters including Joanna Lumley and Michael Palin to the campaign. Human rights campaigner Bianca Jagger, and Booker Prize winner Arundhati Roy, have also spoken out. Charles Darwin’s great great grandson, the anthropologist Dr Felix Padel, has studied, lived with and championed the cause of the Dongria for years.

Join the mailing list

More than one hundred and fifty million men, women and children in over sixty countries live in tribal societies. Find out more about them and the struggles they’re facing: sign up to our mailing list for occasional updates.

News from the Dongria Kondh

“Brazen and shameless:” outrage as controversial Indian mining company opens tribal school

A controversial Indian mining company has opened a school for tribal children in an effort to “transform” them.

India: Tribal leader dies in police custody – as tribe denounce harassment campaign

Dongria Kondh activist in India dies, as fellow leaders harassed on baseless political charges.

Indian authorities harass tribal leaders

Dongria Kondh tribal leaders paraded in front of media, forced to 'surrender' under politically motivated charges

India: Mining company targets Dongria’s sacred hills - AGAIN

Odisha Mining Company makes yet another attempt to mine in Nyamgiri hills despite opposition from tribe

Dongria celebrate recent court victory over mining company

Dongria hold festival to celebrate recent court victory over Odisha Mining Company

Victory for Dongria as Supreme Court quashes new mining attempt

Dongria celebrate court's rejection of new efforts to mine in their hills