YANOMAMI HEALTH EMERGENCY

The Yanomami are being killed as their territory is invaded by thousands of illegal gold miners. President Lula has declared it “a genocide.”

Sign up for the latest updates and to join the campaign.

The Yanomami

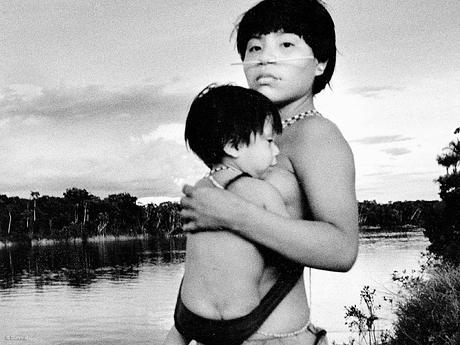

The Yanomami are the largest relatively isolated tribe in South America. They live in the rainforests and mountains of northern Brazil and southern Venezuela.

Like most tribes on the continent, they probably migrated across the Bering Straits between Asia and America some 15,000 years ago, making their way slowly down to South America. Today their total population stands at around 45,000.

At over 9.6 million hectares, the Yanomami territory in Brazil is twice the size of Switzerland. In Venezuela, the Yanomami live in the 8.2 million hectare Alto Orinoco – Casiquiare Biosphere Reserve. Together, these areas form the largest forested Indigenous territory in the world.

The Yanomami first came into sustained contact with outsiders in the 1940s when the Brazilian government sent teams to delimit the frontier with Venezuela.

Soon the government’s Indian Protection Service (as it was then called) and religious missionary groups established themselves there. This influx of people led to the first epidemics of measles and flu in which many Yanomami died.

© Steve Cox/Survival

© Steve Cox/Survival

In the early 1970s the military government decided to build a road through the Amazon along the northern frontier. With no prior warning bulldozers drove through the community of Opiktheri. Two villages were wiped out from diseases to which they had no immunity.

The Yanomami continue to suffer from the devastating and lasting impacts of the road which brought in colonists, diseases and alcohol. Today cattle ranchers and colonists use the road as an access point to invade and deforest the Yanomami area.

The gold rush and genocide

During the 1980s, the Yanomami suffered immensely when up to 40,000 Brazilian gold-miners invaded their land. The miners shot them, destroyed many villages, and exposed them to diseases to which they had no immunity. Twenty percent of the Yanomami died in just seven years.

After a long international campaign led by Davi Kopenawa Yanomami, Survival and the CCPY (Pro Yanomami Commission), Yanomami land in Brazil was finally demarcated as the ‘Yanomami Park’ in 1992 and the miners expelled.

© FUNAI

© FUNAI

However, after the demarcation gold-miners returned to the area, causing tensions. In 1993, a group of miners entered the village of Haximú and murdered 16 Yanomami including a baby.

After a national and international outcry a Brazilian court found five miners guilty of genocide. Two are serving jail sentences whilst the others escaped.

This is one of the few cases anywhere in the world where a court has convicted people of genocide.

The gold mining invasion of Yanomami land continues. The situation is Venezuela is very serious, and Yanomami have been poisoned and exposed to violent attacks for several years. The authorities have done little to resolve these problems.

Indigenous people in Brazil still do not have proper ownership rights over their land – the government refuses to recognise tribal land ownership, despite having signed the international law (ILO Convention 169) guaranteeing it. Moreover, many figures within the Brazilian establishment would like to see the Yanomami area reduced in size and opened up to mining, ranching and colonisation.

Way of life

© Dennison Berwick/Survival

© Dennison Berwick/Survival

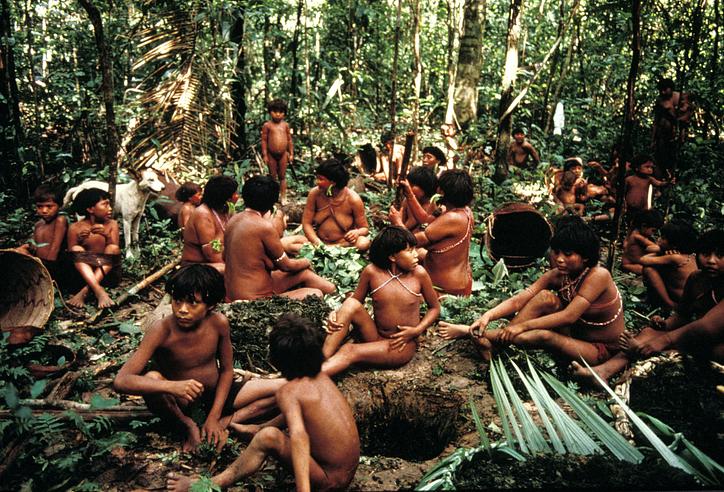

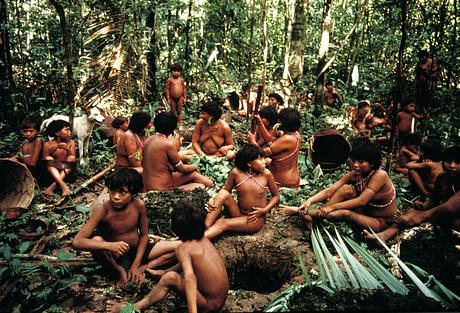

The Yanomami live in large, circular, communal houses called yanos or shabonos. Some can house up to 400 people. The central area is used for activities such as rituals, feasts and games.

Each family has its own hearth where food is prepared and cooked during the day. At night, hammocks are slung near the fire which is stoked all night to keep people warm.

The Yanomami believe strongly in equality among people. Each community is independent from others and they do not recognize ‘chiefs’. Decisions are made by consensus, frequently after long debates where everybody has a say.

Like most Amazonian tribes, tasks are divided between the sexes. Men hunt for game like peccary, tapir, deer and monkey, and often use curare (a plant extract) to poison their prey.

Although hunting accounts for only 10% of Yanomami food, amongst men it is considered the most prestigious of skills and meat is greatly valued by everyone.

No hunter ever eats the meat that he has killed. Instead he shares it out among friends and family. In return, he will be given meat by another hunter.

Women tend the gardens where they grow around 60 crops which account for about 80% of their food. They also collect nuts, shellfish and insect larvae. Wild honey is highly prized and the Yanomami harvest 15 different kinds.

Both men and women fish, and timbó or fish poison is used in communal fishing trips. Groups of men, women and children pound up bundles of vines which are floated on the water. The liquid stuns the fish which rise to the water’s surface and are scooped up in baskets. They use nine species of vine just for fish poisoning.

The Yanomami have a huge botanical knowledge and use about 500 plants for food, medicine, house building and other artefacts. They provide for themselves partly by hunting, gathering and fishing, but crops are also grown in large gardens cleared from the forest. As Amazonian soil is not very fertile, a new garden is cleared every two or three years.

Shamanism and feasts

The spirit world is a fundamental part of Yanomami life. Every creature, rock, tree and mountain has a spirit. Sometimes these are malevolent, attack the Yanomami and are believed to cause illness.

Shamans control these spirits by inhaling a hallucinogenic snuff called yakoana. Through their trance like visions, they meet the spirits or xapiripë. Davi Kopenawa, a shaman explains:

‘Only those who know the xapiripë can see them because the xapiripë are very small and bright like light. There are many, many xapiripë, thousands of xapiripë like stars. They are beautiful, and decorated with parrot feathers and painted with urucum (annatto) and others have oraikok, others have earrings and use black dye and they dance very beautifully and sing differently.’

© Claudia Andujar/Survival

© Claudia Andujar/Survival

As is typical of hunter gatherers and shifting cultivators, it takes the Yanomami less than four hours work a day on average to satisfy all their material needs. Much time is left for leisure and social activities.

Inter-community visits are frequent. Ceremonies are held to mark events such as the harvesting of the peach palm fruit, and the reahu (funeral feast) which commemorates the death of an individual.

Latest threats

Thousands of gold-miners are now working illegally on Yanomami land, transmitting deadly diseases like malaria and measles and polluting the rivers, fish and forest with mercury. Some Yanomami living in communities near mining hotspots have dangerously high levels of mercury in their bodies.

Cattle ranchers are invading and deforesting the eastern fringe of their land.

Yanomami health is suffering and critical medical care is not reaching them, especially in Venezuela.

The Brazilian congress is currently debating a bill which, if approved, will permit large-scale mining in Indigenous territories. This will be extremely harmful to the Yanomami and other remote tribes in Brazil.

The Yanomami have not been properly consulted about their views and have little access to independent information about the impacts of mining.

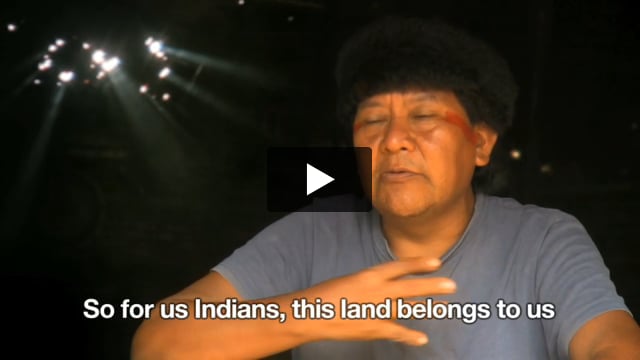

Davi Kopenawa, a leading Yanomami spokesman and President of Hutukara Yanomami Association, warns of the dangers.

‘The Yanomami people do not want the national congress to approve the law or the president to sign it. We do not want to accept this law.’

‘Our land has to be respected. Our land is our heritage, a heritage which protects us.’

‘Mining will only destroy nature. It will only destroy the streams and the rivers and kill the fish and kill the environment – and kill us. And bring in diseases which never existed in our land.’

Uncontacted Yanomami

Yanomami have reported seeing uncontacted Yanomami, whom they call Moxihatetea, in the Yanomami territory. The Moxihatetea are believed to be living in the part of the Yanomami territory with the highest concentration of illegal goldminers. Hutukara has released aerial photos and video of their yano – their communal house.

© Guilherme Gnipper Trevisan/FUNAI/Hutukara

© Guilherme Gnipper Trevisan/FUNAI/Hutukara

The Moxihatetea live in a region of the Yanomami territory with the highest concentration of illegal goldminers, some of whom are operating only kilometers from the yano.

Contact with the miners could be very dangerous for the Moxihatetea, as violent conflict could erupt. The miners also spread malaria and other diseases, which could be fatal for the Moxihatetea who will not have built up immunity to common diseases. In 2018 the Yanomami demanded the authorities investigate reports that miners murdered two Moxihatetea. But no miners have been brought to account.

Due to government cuts, FUNAI – the Brazilian government’s Indigenous affairs department – closed its base near the Moxihatetea. A public prosecutor has ordered FUNAI to reopen it.

Davi Kopenawa said, ‘There are many uncontacted Yanomami. I don’t know them, but I know they are suffering just like we are… I want to help my uncontacted relatives who have the same blood as us. It is really important for all Indigenous people, including the uncontacted people, to stay on the land where we were born.’

Yanomami resistance and organization

As a result of increasing contact and interaction with outsiders and faced with serious attacks on their rights, the Yanomami have formed regional organizations to advocate for their rights. In 2004, Yanomami from 11 regions in Brazil met to form Hutukara (meaning ‘the part of the sky from which the earth was born’), to defend their rights and run their own projects. Yanomami in Venezuela formed their own organization called Horonami in 2011 and Yanomami in other regions in both countries have set up similar organizations.

How does Survival help?

Survival has supported the Yanomami for decades. We led the international campaign for the demarcation of Yanomami territory, along with Davi Kopenawa and the Pro-Yanomami Commission (CCPY), a Brazilian organization. We have also supported their health and education projects. We are fighting alongside the Yanomami and Indigenous peoples across Brazil for their territories to be free of invasions, so they can survive and live in the way they choose. Please join us!

Please join us:

- Email Brazil’s government to demand a halt to mining and to the destruction of the Yanomami’s territory

- Get active! Use this kit to spread the word and push for change

- Get involved with the global movement in many more ways

© Victor Englebert/Survival

© Victor Englebert/Survival

Join the mailing list

There are more than 476 million Indigenous people living in more than 90 countries around the world. To Indigenous peoples, land is life. Find out more about them and the struggles they’re facing: sign up to our mailing list for occasional updates.

News from the Yanomami

Venezuela: Yanomami people engulfed in worst health crisis for decades

The Yanomami people in Venezuela are engulfed in a full-blown health crisis.

Brazil: Crisis in Yanomami territory, one year after operation to remove goldminers

A health crisis is ravaging the Yanomami people in Brazil’s northern Amazon, one year on from emergency operation.

Violence, death and disease still afflict Yanomami in Brazil

Six months on since the Brazilian government launched its emergency operation to address the humanitarian crisis in the Yanomami Territory.

At last! Brazil’s government launches major operation to evict miners from Yanomami territory

In Brazil, Ibama agents and others are stepping in to remove thousands of illegal goldminers from the Yanomami Indigenous Territory.

Survival International statement on Yanomami health emergency: a genocide foretold

Survival proposes a new six-point plan to stop the genocide of the Yanomami people.

New report reveals shocking health crisis for Brazil’s Yanomami tribe

A devastating new report has revealed the crisis in the Yanomami territory caused by a massive invasion of illegal goldminers.