Ingenious skills of tribal peoples

From the hunting peoples of Canada to the hunter-gatherers of Africa, tribal peoples have found ingenious ways of surviving over thousands of years.

During the dry season, the Jarawa use the sap of rattan palms as a source of liquid.

When they collect honey from wild bees, they spit the sap of a plant over the hive to drive the bees away.

© Salomé/Survival

The Moken ‘sea gypsies’ of the Andaman Sea have developed the unique ability to focus under water, in order to dive for food on the sea floor. Their sight is 50% more acute than Europeans’.

© James Morgan/Survival

The Moken’s oral history is rich in knowledge of the sea, winds and lunar cycles.

One legend tells of the la-boon, or ‘the wave that eats people’. The story has it that just before the la-boon arrives, the sea recedes.

When the waves receded prior to the Asian tsunami of 2004, the elders of a Moken village in Thailand recognized the signs and led their community and tourists safely to higher ground.

© Cat Vinton/Survival

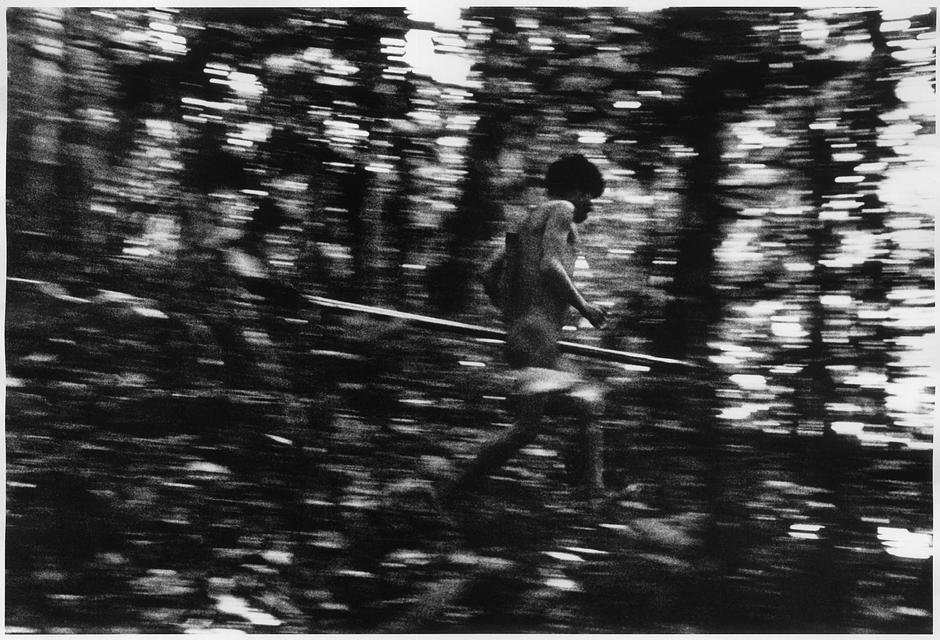

In the rainforests of Borneo, Penan men hunt wild boar with blowpipes made from hardwood and darts laced with tajem, a poison extracted from the milky latex of a tree.

The poison interferes with the functioning of the animal’s heart.

Amazon blow-guns can be longer than two and a half metres.

© Victor Barro/Survival

Until the 1960s all Penan people lived as nomads, communicating with different groups when on the move in the rainforest through a complex signal system of stick and leaf symbols they call oroo.

Oroo relayed such messages as, the person passing here was unwell, or the person who passed here was hungry.

© Survival International

Since the 1970’s, the Penans ancestral lands have been bulldozed, burned and cleared for large-scale logging, oil-palm plantations, gas pipelines and hydroelectric dams.

© Robin Hanbury-Tenison/Survival

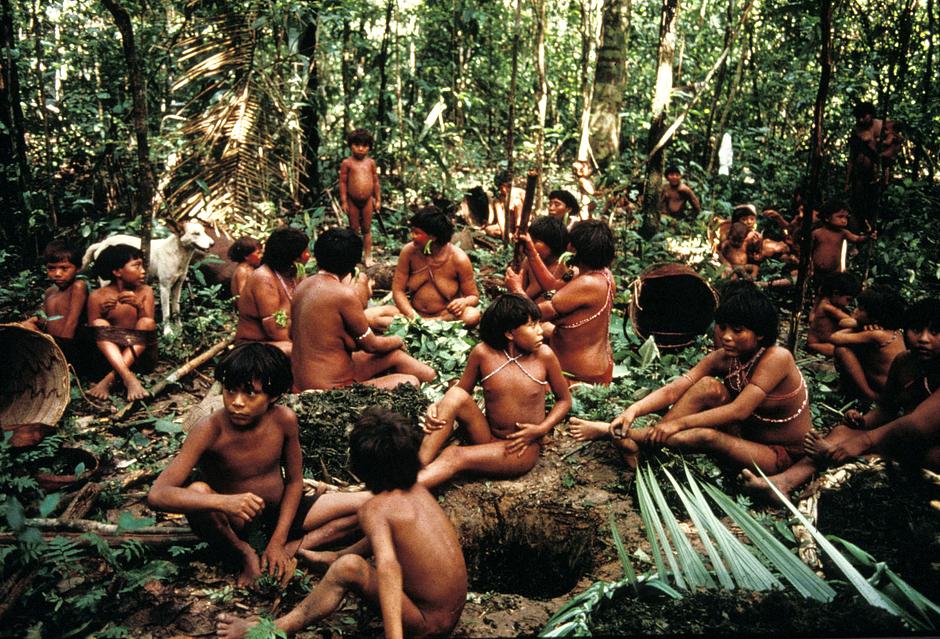

Many tribal peoples have an encyclopaedic knowledge of native animals, plants and herbs; the Yanomami, for example, use around 500 species of plants on a daily basis.

The Yali people of West Papua excel as ecologists, and recognize at least 49 varieties of the sweet potato and 13 varieties of bananas.

© William Milliken/Survival

Over time, tribal peoples have developed complex, holistic health systems.

The bark of the copal tree is applied to eye infections, the juice of cat’s claw vine is used to treat diarrhoea, and crushed aromatic leaves are inhaled to alleviate colds and nausea.

Many of the drugs used in western medicine today originate with tribal peoples, and have saved millions of lives. The poison curare, which Yanomami hunters have long used on the tips of arrows to paralyze prey, has been appropriated by western medicine as a muscle relaxant.

© Fiona Watson/Survival

Most tribal peoples are sensitively attuned to animal behavior. ‘Pygmy’ men are such proficient mimics they can imitate the sound of a distressed antelope in order to lure another out of the bush.

Similarly, Siberian hunters are able to mimic the cry of a reindeer calf looking for its mother or the bark of a rutting male.

© Kate Eshelby/Survival

Awá women care for different species of orphaned baby monkeys, including howler and capuchin, by suckling them.

© Domenico Pugliese/Survival

Awá women also extract the resin of the Brazilian redwood tree (maçaranduba tree) to light houses at night.

Today, their forests are being illegally logged and the Awá have become the Earth’s most threatened tribe; they live under the threat of extinction due to violent attacks and the theft of their land.

© Domenico Pugliese

Reindeer meat is the most important part of the Nenets’ diet.

It is eaten raw, frozen or boiled, together with the blood of a freshly slaughtered reindeer, which is rich in vitamins.

The fat content of reindeer milk is 22%; six times as much as that of a cow.

The bowstrings of the Hadza tribe of Tanzania are made from animal ligaments; the arrows meticulously crafted from kongoroko wood and fletched with guineafowl feathers.

The sap of the desert rose shrub is used to coat the arrow tips in poison.

© Jean du Plessis/Wayo Africa

The Hadza have developed a mutually helpful relationship with the honeyguide bird, which leads them to wild bees’ hives.

The bird calls to the hunters, who whistle back to it. It flits from tree to tree, stopping to wait for hunters to catch up, so eventually leading them to a hive, often high in the boughs of a baobab tree.

© Joanna Eede/Survival

Hadza hunters then climb the tree with burning grass, to smoke out the bees from the hive.

The bird is rewarded with the honeycomb leftovers.

You can walk all the way to Ndabuado, and the honeyguide finds you and brings you back to the hive you just walked past, says Johana, a Hadza hunter.

© Joanna Eede / Survival

A Bushman woman in Botswana chews the flesh of a melon for its moisture.

Traditionally, the Bushmen find water in ‘pans’ – rain-filled depressions in the sand – and from plants such as tsamma melons and roots, techniques learned over thousands of years of surviving in the desert during the dry seasons, when the water-holes of the Kalahari sand-face turn to dust.

You learn what the land tells you, says Gana Bushman Roy Sesana.

© Dominick Tyler

Leave no trace behind.

Tribal peoples perhaps still know better than most that the delicate balance of man and nature has only been maintained for millennia through a respect for its limits. It is no coincidence that many areas that are the richest in biodiversity remain so due to the care of their tribal guardians.

The Awá leave little sign of having passed through the forest other than disturbed liana leaves and marks on tree trunks; the Yanomami’s fish poison breaks down rapidly in the water, leaving no pollution; the Innu carefully preserve caribou leg bones and hang antlers high in trees as a mark of respect to the animal.

Responsibility and reciprocity are vital requirements for survival; to take more than is needed or to degrade the earth is not only self-defeating, but a neglect of their unborn children. We hunt selectively, say the Penan. We only hunt for our needs.

Without the land rights for which Survival has been campaigning for 44 years, however, tribal peoples will not survive.

Survival’s work allows tribal peoples to defend their lives, protect their lands, determine their own futures and ensures that their extraordinary skills and knowledge, so relevant today, are not lost to the world.

© TH/Survival

For many tribal peoples, continuous immersion in nature over thousands of years has resulted in a profound attunement to the subtle cues of the natural world.

Acute observations have taught tribes how to hunt wild game and gather roots and berries, how to sense changes in climate, predict movements of ice sheets, the return of migrating geese and the flowering seasons of fruit trees.

Sophisticated hunting, tracking, husbandry and navigation techniques have also been the ingenious responses of tribal peoples to the challenges of varied, and often hostile, environments.

The development of such observations and skills is not only testament to the latent creativity of humans and their extraordinary ability to adapt, but has also ensured that when living on their lands, employing the techniques they have honed over generations, tribal peoples are typically healthy, self-sufficient and happy.

I am the environment, said Davi Kopenawa Yanomami. I was born in the forest. I know it well.

© Claudia Andujar/Survival

Other galleries

“We, the People” 2020 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International “We...

“We, the People” 2019 - The 50th anniversary Calendar

Our “We, The People” 50th Anniversary Calendar features stunning portraits of...

"We, the People" 2018 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International "We...