The Hunt

Who are the world’s hunter-gatherers? Where do they live and what threats do they face? Which tribe uses the poison well known to western crime-writers, and why might it be more correct to call them ‘gatherer-hunters’?

A Yanomami hunter darts through the Amazon rainforest.

A common misconception about hunter-gatherers has existed for centuries, which holds that there exists a human evolutionary hierarchy, in which ‘backward’ hunters-gatherers lie somewhere near the bottom and the more sophisticated, or advanced, agriculturalists near the top.

Largely a colonial myth, this theory has been used over millennia to justify the theft of tribal territories, says Stephen Corry, Director of Survival International. Some hunter-gatherer societies have failed to survive changes in their environment, but others have flourished, and will continue to thrive, if their human rights are respected and their land rights recognised.

Today’s hunter-gatherers are not remnants of human history. They are some of the world’s only egalitarian societies, and equality between age groups and genders, as well as with the environment, is often highly valued.

They have adapted to changing climates and eco-systems and developed an extraordinary repertoire of tactics and tools that probably bear little resemblance to the way prehistoric peoples lived 10,000 years ago.

© Claudia Andujar/Survival

The ways of life of today’s hunter-gatherers reflect not only the ingenuity of their own societies, but the latent creativity of human beings.

Hunting demands agility, patience, knowledge and intricate skills passed down the generations. It provides sustenance for families, is often the well-spring of male prestige and can determine the collective identity of a people. We hunt and trap, said Innu Elder, Joe Pinette. That’s what the Innu do.

Great ingenuity is required, says Stephen Corry. A hunting tribesman combines the skills of master craftsman, consummate athlete and astute strategist.

And universal to all hunters is the prestige inherent in the hunt. Hunters love hunting, says Corry. It is far more than about finding food.

A good hunter views it as as one of life’s supreme accomplishments.

© Survival International

Hunters learn their craft at a young age.

Yanomami boys in the Brazilian Amazon learn to ‘read’ the footprints of animals and shin up trees by tying their feet together with liana vines; Yanomami girls help their mothers cultivate crops such as manioc in their gardens, and carry water from the rivers.

Young Bushman boys in Botswana are given toy bows and arrows to hunt rats and small birds, and are taught to kill hare or make blankets from gemsbok skin. Girls as young as five help their mothers gather plants, berries and tubers.

Children of the Piaroa tribe, who live along the banks of Venezuela’s Orinoco River, hunt enormous bird-eating tarantula spiders, which they roast over a fire.

I grew up a hunter, said Roy Sesana, a Gana Bushman from Botswana. All our boys and men were hunters.

© Mark Hakansson/Survival

Over generations, the lives of many hunter-gatherer tribes have been devastated by invading colonists, racist governments and corporations determined to profit from their lands.

The Innu of north-eastern Canada spent thousands of years as nomadic hunter-gatherers, following great herds of migrating caribou across Nitassinan, their vast sub-arctic homeland.

In the 1950s and ’60s they were pressured by the government and Catholic church into settling in fixed communities. Much of their land was confiscated, and hunting for caribou – the essence of their identity as a people – was strictly regulated.

An entire way of life was destabilised; the human consequences were disastrous.

Several years ago, when an Innu man was asked his occupation, he said hunter, said Jean Pierre Ashini, an Innu man from Canada.

Now, he says unemployed.

© Joanna Eede/Survival

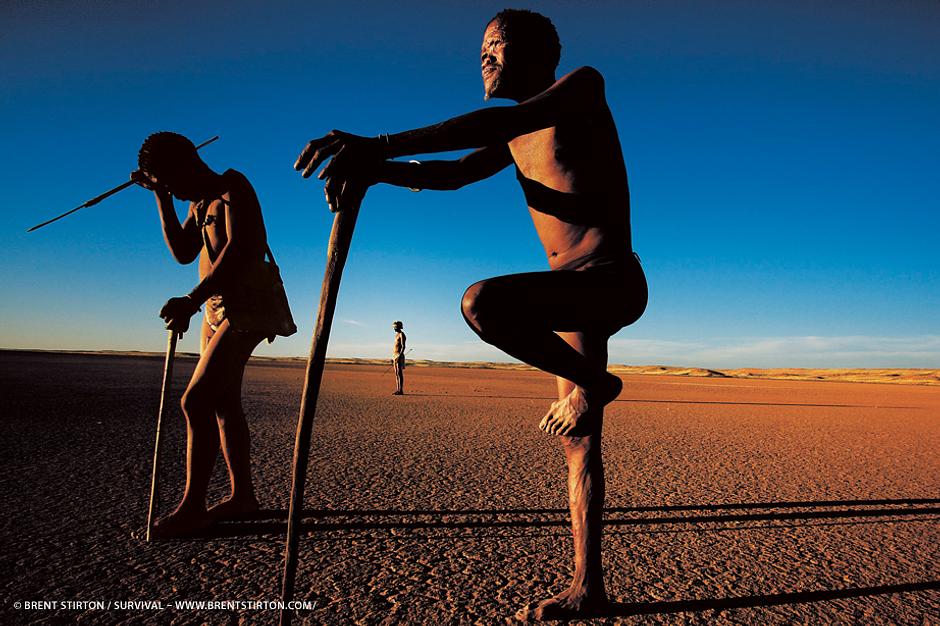

Similarly, the Bushmen – the indigenous peoples of Southern Africa – lived on their lands as hunter-gatherers for tens of thousands of years.

Today, the last of the hunting Bushmen live in Botswana’s Central Kalahari Game Reserve where hunting involves arrowing the game, then chasing it for many hours – often in intense heat – until the prey collapses.

You set a trap or go with bow and spear says Bushman Roy Sesana. You track the antelope. It can take days. He knows you are there. But he runs and you have to run. It can last hours and exhaust you both.

The Bushmen of the reserve have been persecuted by the Botswana government for many decades. Their right to live and hunt on their ancestral lands has been denied them.

In three big clearances between 1997 and 2005, virtually all the Bushmen were evicted by force out of the reserve into resettlement camps.

Today, they are rarely able to hunt. In 2014, hunting was banned in Botswana, which is causing additional hardship for the Bushmen: those who try to hunt are routinely arrested and beaten.

© Brent Stirton/Survival

I am living on sand, I am walking on sand, I am looking for footprints on sand, and I have seen this animal’s tracks on sand, so I have killed this animal while we were both running on sand.

You think how hard Kudu is working. You feel it in your own body. You see it in the footprints, she is with you and your legs are not so heavy.

When you feel Kudu is with you, you are now controlling its mind. Its eyes are no longer wild. You have taken Kudu into your own mind.

As it tires, you become strong. You take its energy. Your legs become free. You run fast like yesterday.

Karoha, Bushman, Botswana.

© Dominick Tyler

The Awá tribe are one of the last nomadic hunter-gatherer tribes in Brazil.

They have flourished in the Amazon rainforest for generations by hunting wild pigs, tapirs and monkeys with 6-foot bows, and gathering forest produce such as babaçu nuts, açaí berries and honey.

Over the past four decades, however, they have witnessed the destruction of their homeland and the murder of their people by outsiders. Today, more than 34% of one of their territories has been razed to make way for cattle ranches.

Following Survival’s campaign, the Brazilian authorities are removing the invaders, but for the Awá to survive, the government must protect their lands from further invasions.

© Domenico Pugliese

The Hadza, a small tribe of highly skilled hunter-gatherers, live by the soda waters of Tanzania’s Lake Eyasi.

Until thirty years ago, the Hadza frequently hunted large animals such as zebra, giraffe and buffalo in the dense acacia bushland of their homeland, Yaeda Chini. They shared their home with rhinoceros and lion, elephant and large herds of savannah animals.

Most large mammals have now decreased in number due to encroachment on Hadza land by their pastoralist neighbours; today the Hadza mostly hunt dik-dik (a small antelope), monkeys, bush pig, warthog and impala.

The Tanzanian government has made repeated attempts to ‘settle’ the Hadza. Today, only 300 – 400 of a population of approximately 1,300 Hadza are still nomadic hunter-gatherers, while the rest live part-time in settled villages, supplementing locally bought food with natural produce.

© Joanna Eede/Survival

Hadza women traditionally leave camp most mornings with digging sticks, which they use to uproot deep tubers. They also forage for roots, berries and baobab fruit.

A sexual division of labour is found in most hunter-gatherer tribes. While men hunt large animals, women gather other foodstuffs.

Their mutual dependence on each other’s foods has encouraged the development of egalitarian societies; Hadza women, for example, have a great amount of autonomy and participate equally in decision-making with men.

© Joanna Eede/Survival

Most of the hunter-gatherers’ diet actually comes from gathering – not hunting.

This has prompted some scientists to invert the name to ‘gatherer-hunters’, says Stephen Corry.

It is thought that the ratio of vegetables to meat in the Bushman’s diet is nearly 6:1, and that they eat approximately 80 different plant species.

© Dominick Tyler

The hunter-gatherer tribes of the Andaman Islands – the Jarawa, Great Andamanese, Onge and Sentinelese – are believed to have lived in their Indian Ocean home for up to 55,000 years.

The Jarawa are thought to have ‘optimum’ levels of nutrition. They eat foods such as wild pig, turtle, fish, crab, prawns and molluscs, and supplement them with various wild roots, tubers, nuts, seeds and honey. Fishing in the coral-fringed reefs is carried out with a bow and arrow. They have detailed knowledge of more than 150 plant and 350 animal species.

© Survival

Most hunter-gatherer diets are highly nutritious.

It has been suggested that the development of agriculture actually brought about a protein deficiency, and that human beings shrank after the first adoption of crops.

The evidence found in bones and teeth seems to point to an increase in child deaths and a decrease in average longevity, where farming gradually supplanted hunting, says Stephen Corry.

Today, those hunter-gatherer tribes who refrain from eating processed western foods remain largely unaffected by cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and soaring rates of obesity that are prevalent among industrialised societies.

We Hadzabe have no record of famine in our oral history, said a Hadza man.

The reason is we depend on natural products of the environment.

© Yoshi Shimizu

The Innu of north-eastern Canada traditionally hunted caribou, bear, marten and fox, and small game such as beaver, porcupine, partridges, ptarmigan, ducks and geese.

They fished for trout, salmon and arctic char in the deep lakes, and gathered blueberries and crab apples in the fall.

But after the 1950s, their diet was replaced by a diet high in saturated fats, refined sugars and salt. Obesity became commonplace in their communities, as did its pathological corollary: diabetes, which was relatively rare among the Innu before they were settled.

Studies suggest that this may in part be due to the high content of Omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants in their traditional diet.

When I was a kid, 15 years ago, there was zero diabetes and cancer. Our grandparents were hunting and eating healthy country foods, says Michel Andrew, an Innu man from Sheshatshiu.

© Katie Rich

Hunter-gatherers possess detailed knowledge of their ecosystems’ animals, plants and herbs.

Were it not for the specialized botanical knowledge of many tribal peoples, vital medicinal compounds might still be unknown today; it is thought that plants have been vital in the development of around 50% of today’s prescription drugs.

The Yanomami, for example, routinely utilise around 500 species of plants for building materials, food and medicines. They relieve diarrhoea with the juice of the woody cat’s claw vine and treat eye infections with the bark of the copal tree.

In North America, the manufactured painkiller aspirin was developed from the bark of the white willow tree, which American Indians boiled to treat headaches.

The Innu also have an intimate understanding of their homeland’s plants and animals: the golden sap of spruce trees is used as a glue for canoe-building, an ointment for sunburn and a chewing-gum.

© Survival International

Hunter-gatherers have developed sophisticated hunting, tracking, husbandry and navigation techniques over generations.

The hunter must have an extraordinarily well-tuned understanding of the game animal, says Stephen Corry. He needs to predict accurately its movements and habits. He needs to know where to start looking, and to recognise the subtlest of signs – its tracks on the ground or its smell on a leaf or in the air.

A hunter may mimic a predator in order to frighten it towards a fellow hunter or copy the call of a female in heat, to attract males. ‘Pygmy’ hunters mimic a duiker’s mating call which attracts many different kinds of small antelope. Similarly, Siberian hunters are able to mimic the cry of a reindeer calf looking for its mother or the bark of a rutting male.

The Moken, a semi-nomadic Austronesian people who live in the Mergui Archipelago in the Adaman Sea, have developed the unique skill to focus under water, which allows them to dive for food on the sea floor such as sea-cucumber and crustaceans, which they catch with harpoons, spears and hand-lines.

© Cat Vinton/Survival

The bowstrings of the Hadza tribe of Tanzania are made from animal ligaments; the arrows meticulously crafted from kongoroko wood and fletched with guineafowl feathers.

Hunting weapons include bow and arrow, blowgun, club, spear or harpoon or, nowadays, shotgun or rifle.

Amazon blow-guns can be longer than two and a half metres. Penan blowpipes, called keleput, are approximately 1.8 metres long and are made from hard wood.

Aka ‘pygmies’ trap with vine leaves and hunt with large nets; women also take part, chasing animals out of the bush by singing and shouting.

© Jean du Plessis/Wayo Africa

Crime novelists have written widely about it; the Yanomami and many other Amazonian tribes coat their arrows or darts with it.

‘It’ is ‘curare’, a poisonous mix of different plants which is boiled down to thick glue, smeared on darts and left to dry. As it enters the blood of the smitten bird or animal, it relaxes their muscles. Monkeys can no longer hold branches and birds can no longer fly; eventually, they drop to the ground where they can be killed. Curare has been appropriated as a muscle relaxant in western medicine, and made possible procedures such as open-heart surgery.

Arrow poison is also crucial to the Kalahari Bushmen. It is generally made from crushed beetle larvae or the entrails of a poisonous caterpillar known as n’gwa.

The Hadza use the toxic sap of the desert rose shrub to coat their arrow tips.

© Jerry Callow/Survival

Some Amazon hunter-gatherer tribes also fish by crushing plant poisons, commonly called barbasco, or _timbó, in the water. The poison temporarily stuns fish, which float to the surface, allowing the Indians to scoop them up in baskets. The poison wears off after a while, and the uncaught fish are able to swim away.

The Penan of Sarawak, one of the last hunter-gatherer tribes in Malaysia, similarly release toxins from crushed forest plants into the water to kill fish.

© Survival

For many hunter-gatherers, the hunt also has spiritual and mythical dimensions.

Game animals are highly respected as the sustainers of human life. A common feature is the notion that the hunter comes to an ‘agreement’ with the hunted animal. Hunting is going and talking to the animals, says Bushman Roy Sesana. You don’t steal. You go and ask.

The Innu do not consider hunted animals as prey. They scrupulously share caribou meat and carefully preserve the leg bones; throwing them away is disrespectful to kanipinikat sikueu, the ‘Master’ spirit of the caribou. Antlers are hung high in the trees, as a mark of respect.

Yawanawa myth holds that if a hunter is extremely lucky if he comes across a wild boar with one white leg.

© Joanna Eede/Survival

Complex rules governing hunting protect the resources on which the tribal community depends.

Yaka ‘Pygmies’ relationship with their environment is regulated by the restraint and sharing required by the concept of ekila. If the Yaka do not share properly; if they over-hunt, laugh at hunted animals or eat certain types of animal, their ekila will be ruined. Damaging ekila means hunting may suffer, women might difficulties during childbirth, and children could become ill.

And yet the Yaka, like many tribal peoples, are often criminalized as “poachers” because they hunt their food. As a result they face harassment, beatings and even torture at the hands of anti-poaching squads.

© Kate Eshelby/Survival

The hunter-gatherer mentality is deeply rooted in the human psyche.

Yet the world’s remaining hunter-gatherers, who have lived on their lands for millennia, are still viewed by many as “backward” or somehow “primitive”.

Many tribal peoples have made different choices from most in industrialized societies, preferring to be mobile rather than settled, opting for hunting or herding rather than agriculture, says Stephen Corry. But they are just as contemporary as any other human society.

Their problems arise from land theft, ‘development’ and ‘conservation’ projects and oppressive, racist policies that threaten to wipe them out.

Unless their lands are demarcated and their human rights honoured, their lives will always be in jeopardy, as will many of the extraordinary skills, ideas and beliefs that their ways of life have established.

© Kate Eshelby

In the shadows of the Sarawak rainforest, a Penan hunter brings a blowpipe to his mouth, and with a short, sharp exhalation fires a dart high into the trees.

At one time, everyone relied on foraging and hunting to survive. People hunted wild game, collected plants and adapted successfully to diverse – and often inhospitable – habitats.

Hunter-gatherer societies are still found across the world, from the Inuit who hunt for walrus on the frozen ice of the Arctic, to the Ayoreo armadillo hunters of the dry South American Chaco, the Awá of Amazonia’s rainforests and the reindeer herders of Siberia.

Today, however, their lives are in danger. The issues they are forced to cope with on a daily basis have nothing to do with their innate strength and resourcefulness as a people, but stem from oppressive external threats to their lands, health and ways of life.

© Julien Coquentin

Other galleries

“We, the People” 2020 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International “We...

“We, the People” 2019 - The 50th anniversary Calendar

Our “We, The People” 50th Anniversary Calendar features stunning portraits of...

"We, the People" 2018 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International "We...