Festivals

As global monoculture erodes cultural diversity, the variety of tribal festivals and rituals is a reminder that humans have diverse insights, different priorities, and choose other – successful – ways of living.

For many tribes, life is lived through ritual.

Rituals are held in honor of the lands that sustain tribal peoples and the spirits that watch over them. They mark the passing of seasons, the fertility of crops and the cycles of human life. They are used to purify the earth, set the sun on its seasonal course, encourage the melting snows to irrigate crops and bring success to an Amazonian hunt.

When tribal peoples lose their lands, as they have done for centuries, they lose their livelihoods. But they also lose the bedrock of their identity as a people, and the inspiration for their festivals.

© Eric Lafforgue/Survival

In the land of the blue skies, horses are thought to be the messengers of the gods. Boys are taught to ride before they can walk, learning on silver-engraved saddles that have been passed down the generations.

The biggest Mongolian festival, naadam, is held every year, with horse races up 30 kms long; the jockeys are children aged between six and twelve.

The winning horse is greeted with Tumay ekh, meaning winner of ten thousand; the last is serenaded with an encouraging song, in order to encourage it to win the following year.

© Bruno Morandi/Survival International

Bolivia: on the vast windy plateau of the central Andes, Aymara Indians drink chicha, a drink made from corn and red pepper, during the Aymara festival celebrations.

© Rhodri Jones/Panos Pictures

In the wet season, when the hills of the Serra de Norte are shrouded in clouds, the longest indigenous ritual in Amazonia begins.

Yãkwa maintains the harmony of the world and is a four month exchange of food between the Enawene Nawe and the subterranean yakairiti spirits, who are the owners of fish and salt.

At the beginning of Yãkwa, the Enawene Nawe build waitiwina (dams) across Adowina (the Rio Preto). The dams are created from criss-crossing trunks, which form a latticework of interwoven timber, into which are inserted dozens of cone-shaped traps.

Bark and vine are used as joints.

© Fiona Watson/Survival

In the first light of dawn, Enawene Nawe men of Mato Grosso state in Brazil gather outside haiti: the house of sacred flutes.

They have recently returned from camps in the rainforest, in order to celebrate the most important fishing ceremony of the year: the Yãkwa banquet.

The Enawene Nawe are expert fishermen. In the dry season, they catch fish with a poison called timbó, made from the juice of a woody vine. Bundles of vines are pounded in the water, so releasing the poison and asphyxiating the fish, which then rise to the surface.

© Fiona Watson/Survival

The climax of the festival is a lavish banquet during which salt, manioc and honey are exchanged with the yakairiti spirits.

The men’s waists are wrapped in palm fibres, their necklaces strung with red macaw, curassow and hawk feathers. They move around a circle in slow steps, their chanting accompanied by the deep piping of bamboo flutes.

For the last few years however, the tribe has struggled to carry out Yãkwa, due to the decline in fish stocks from deforestation and hydro-electric dam construction. The UN body UNESCO recently called for the urgent safeguarding of the Yãkwa ritual, referring to it as an intangible cultural heritage.

When I was a small boy, I always came to the dams with my father, said Kawari, an Enawene Nawe elder.

We let the fish go up the river to lay their eggs. But if hydro-electric dams are built all the eggs will disappear and the fish will die.

© Fiona Watson/Survival

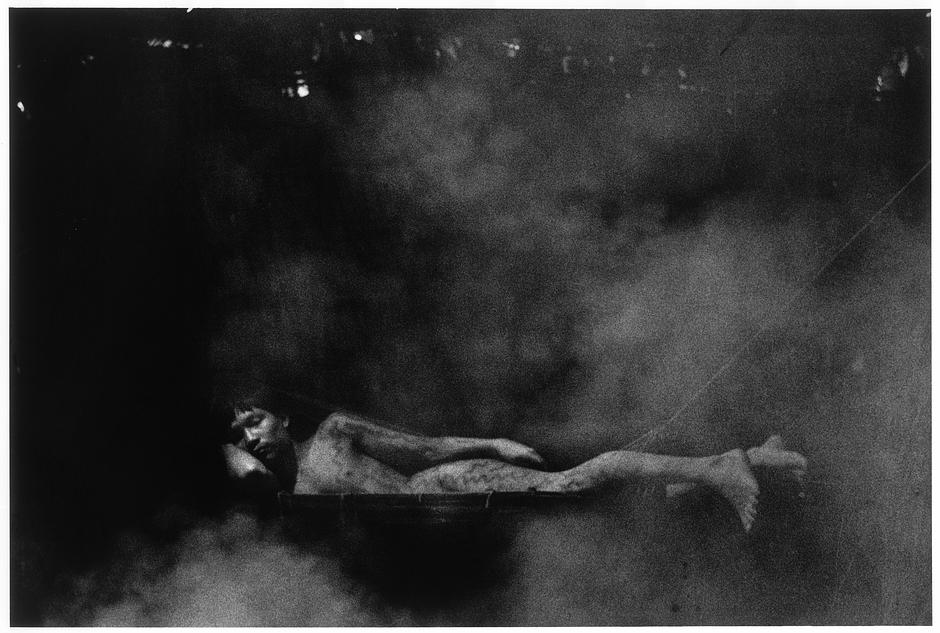

The Awá tribe of Brazil live between the equatorial forests of Amazonia to the west and the eastern savannahs.

During their full moon ritual, men leave Earth behind as they travel to the iwa, the domain of the earth spirits. Their dark hair speckled white with king vulture feathers, the men commune with the spirits through a chant-induced trance, during a sacred ritual that lasts until dawn.

© Lewis Davies/Survival

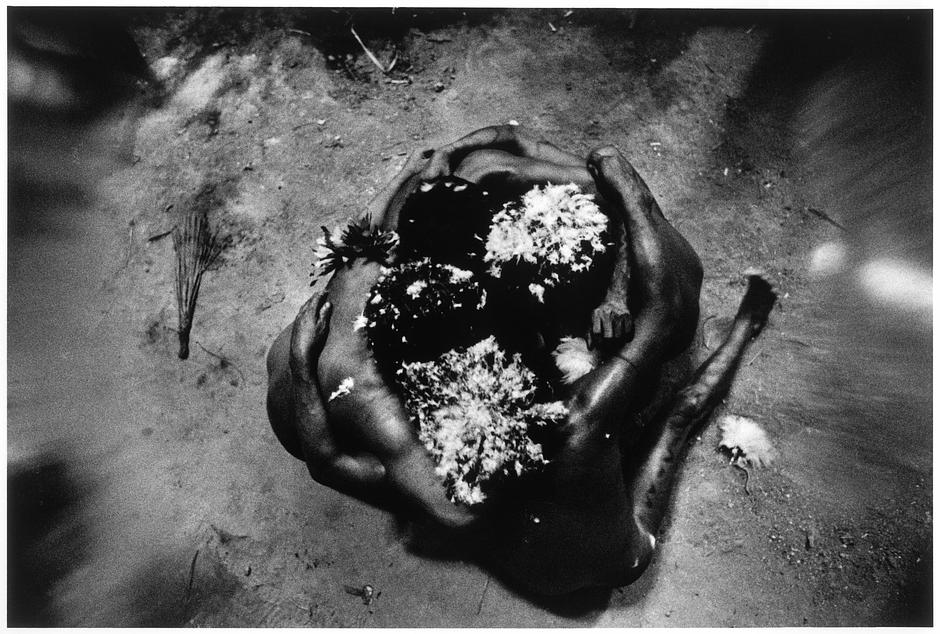

For the journey to the forest spirits, Awá wives decorate their husbands with king vulture feathers, using tree resin as glue.

But their trees are dying: the rainforests of the Awá are disappearing faster than in any other indigenous area in the Brazilian Amazon. More than 30 percent of one of their territories has now been razed over the course of four decades to make way for cattle ranches.

In the process the Awá have also witnessed the murder of their people at the hands of karaí, or non-Indians.

© Toby Nicholas/Survival

A Brazilian federal judge recently described the Awá’s situation as genocide.

They are now the Earth’s most threatened tribe.

© Lewis Davies/Survival

The Niyamgiri Hills form an area of densely forested hills, deep gorges and cascading streams in Odisha state, eastern India.

The region is home to the Dongria Kondh people. The 8,000 Dongria know no other life; for generations their physical and cultural survival has depended on a symbiotic relationship with their natural environment.

To be a Dongria Kondh is to farm the hills’ fertile slopes, harvest its produce and worship the mountain god Niyam Raja Penu and his throne Niyam Dongar, the 4,000 meter Mountain of Law.

During harvest festivals, Dongria Kondh sacrifice buffalo to their god, and a holy man runs over hot coals. Niyam Raja is our god and we worship him, said a Dongria man. We worship the rocks, the hills, our houses and our villages.

© Sanjit Das/Panos Pictures

When the air is filled with the dusty smell of turmeric and young women have used the spice to stain their arms a rich yellow, it is the time of a Dongria Kondh wedding.

With flowers in their hair and coloured bands around their necks, men and women whirl and spin in circles. At dusk, the veiled bride emerges from her family home and is escorted through the darkening forest to the groom’s village.

The wedding guests follow, dancing, beating their hand-made drums and singing long into the night.

© Jason Taylor/Surviival

The Dongria Kondh’s way of life is now threatened by mining company Vedanta Resources, which has long had its sights set on mining the bauxite that lies under Niyamgiri Hills.

Vedanta’s open-cast mine would gouge out the summit of Niyam Dongar, destroy Niyamgiri’s forests, disrupt the rivers, and spell the end of the Dongria Kondh as a flourishing, distinct people.

But in a landmark ruling, the Indian government blocked the development of the mine. This success was due to the heroic determination of the Dongria, strong national support for their cause and the international campaigning by Survival and others.

© Jason Taylor/Survival

Tribal festivals also honor the different cycles of human life.

In East Africa, a young Maasai boy blows into the spiraling horn of a greater kudu antelope to summon morans for the e unoto ceremony, which heralds the transition of the teenage moran into manhood.

The ceremony involves several days of singing and dancing.

© Caroline Halley des Fontaines/Survival

Large areas of Maasai land in Tanzania have already been taken over, for private farms, government projects, wildlife parks or private hunting concessions. In March 2013, the Tanzanian government announced a new ‘conservation’ area on Maasai lands in Loliondo.

Maasai community leader Samwel Nangiria told Survival that this will spell the end of the Maasai and the Serengeti ecosystem.

Our ancestors lead their people beyond their farthest horizons. Their strength and might may be seen in our legends. We must not follow the way of those races of men who have vanished from the surface of the earth.

We have our culture behind us, and our courage, pride and noble truth.

Lemeikoki Ole Ngiyaa.

© Caroline Halley des Fontaines/Survival

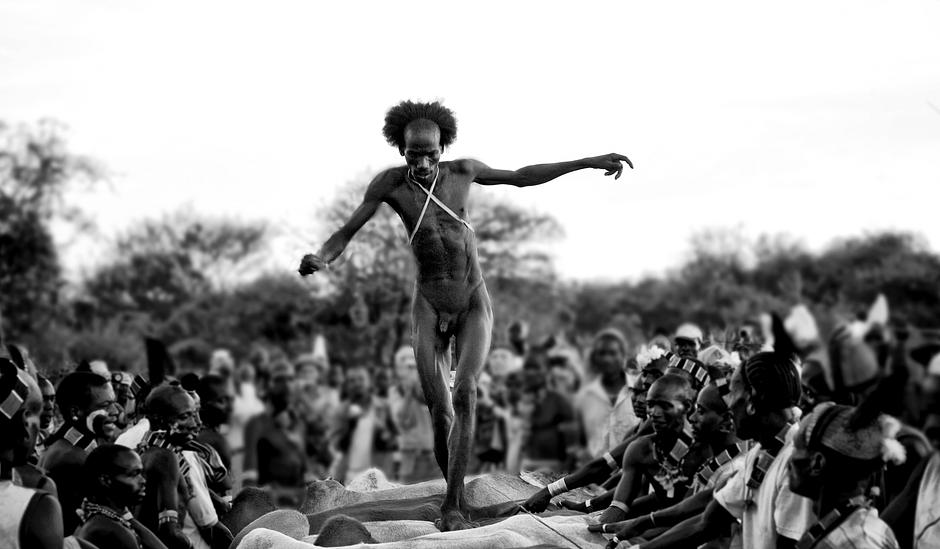

In Ethiopia, before a Hamar man can marry, he needs to race over a line of cattle.

Smeared with dung to give him strength – the cattle are also covered in dung, which makes them slippery – a man must run over up to 30 cattle four times, without falling. If successful, the man becomes a Maza; men who have successfully completed this rite of passage.

The Hamar and other tribes have lived in the Lower Omo valley for centuries; the region is believed to have been a cultural crossroads for thousands of years, where a vast diversity of migrating peoples have converged.

© Mario Gerth/Survival

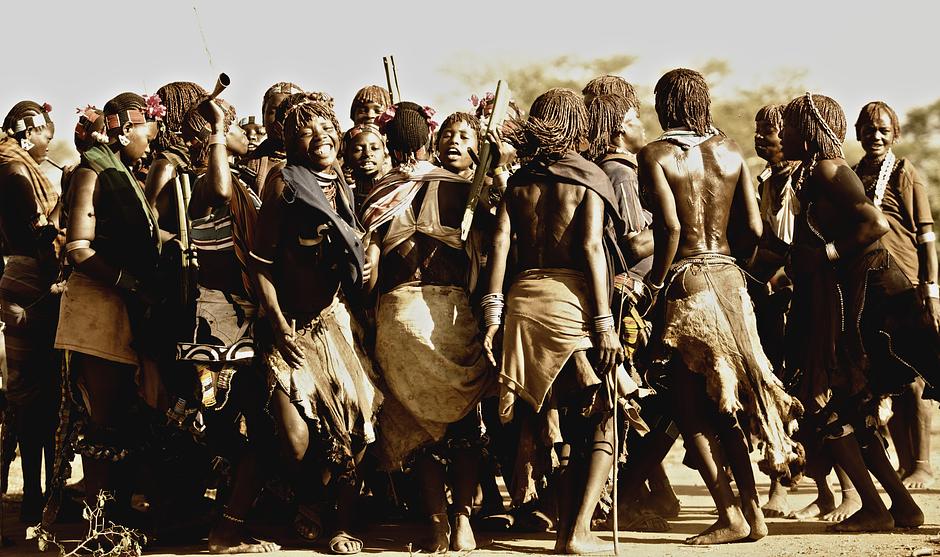

Before the cattle-jumping ceremony, Hamar female women blow their horns and shout taunts to the Mauza, a group of men who have already completed the ceremony, and who will whip the women. Hamar women regard the scars as a proof of devotion to their husbands.

Today, however, the tribes are threatened by a massive hydroelectric dam, and associated land grabs for plantations. The dam will block the southwestern part of the river, so ending its natural flood cycle and jeopardizing the tribes’ flood-retreat cultivation methods.

There is no singing and dancing along the Omo River now, a tribesman told Survival. The people are too hungry. The kids are quiet.

© Ingetje Tadros/ingetjetadros.com

The spirit world is an ever-present and integral part of life for many tribal societies.

Yanomami shamans (xapiripë thëpë) are guided by spirits (xapiripë) and the wisdom of their ancestors. They command thunder storms and caution the winds, prevent the sky from falling down and use their powers to ensure hunting successes, cure human diseases and put flight to hostile spirits.

The shamans give orders to the sun, and instruct the spirits to speak to the moon.

© Claudia Andujar/Survival

Most Yanomami rituals are flourishing: Survival led the successful international campaign for the demarcation of Yanomami territory.

The xapiripë have danced for shamans since the very beginning of time, and they continue to dance today.

Their heads are covered with white hawk down, and they wear black bands made of monkey tails and turquoise cotinga feathers in their ears.

They dance in a circle, unhurriedly.

© Claudia Andujar/Survival

Dance is one vibrant expression of tribal peoples’ spiritual beliefs.

In the narrow valleys of the Hindu Kush in Pakistan, the Kalash people celebrate the winter solstice with the festival of choimus.

Girls wearing costumes decorated with cowrie shells, and necklaces made from apricot kernels, dance around bonfires singing hymns to the spirit of Balomain and offer seasonal foods to their ancestors.

© David Stewart-Smith/Survival

He was born a dancer and had a dance for everything.

He danced birth; he danced adolescence; he danced his marriage and many another event of life and spirit; he danced the sun leaping into the sky; he danced for the moon under the moon, and finally he danced out the agony of dying.

Laurens van der Post, from The Lost World of the Kalahari.

© Survival

During the Bushman trance dance, dancers circle the fire, clapping and singing rhythmically, the moth cocoons that are tied to their ankles rattling with every step. The euphoria induced by the dance can generate num; a boiling energy.

I dreamed and the dancing and healing started, said Xlarema Phuti, a Bushman woman. When I started to dance the trance dance I could feel a person by their blood and smell, and I would go to that person and start healing them. When I fall down, I feel the blood of the ancestors and talk with them.

The ancestors speak through my blood. I feel something happening, something spiritual. I can see the ancestors with my eyes when I’m talking to them in the trance dance.

© Survival

Tragically, the Bushmen of southern Africa are the most victimized peoples in their region’s history.

They were hunter-gatherers for millennia, but when diamonds were discovered on their ancestral lands in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR), many were forcibly removed from their homes. They were driven to eviction camps outside the reserve, where prostitution, depression, alcoholism and HIV – problems they had never before encountered – are now rife.

I invite the world to study my and other Bushmen’s history to understand how our attachment to and love of the land, and all that it nurtures has helped us survive all the trials we’ve been called upon to endure, said Bushman Dawid Kruiper.

© Survival

When tribal peoples are evicted from their homes; when their lands are destroyed in the name of ‘progress,’ their suffering is obvious: alcoholism, chronic diseases, infant mortality and unemployment are, more often than not, the effects of being forcibly assimilated into mainstream societies.

When tribal peoples are torn away from the lands that inspire their songs, dances, myths and memories, deep depression often follows. These are the creative touchstones by which they know themselves; the rituals represent a myriad imaginative ways of interpreting life. Without their homelands, the fabric of their identity collapses.

When the Bushmen dance to the rhythmic beat of the trance dance, when the Hopi sing for snow and the Enawene Nawe take up their flutes at dawn, they are celebrating their connections to each other, and to the Earth. Separation from their lands is catastrophic, but the solution to their problems – the recognition of land rights, for which Survival has campaigned for over forty years – is simple.

© Eric Lafforgue/Survival

I have built my house on the earth and my children and grandchildren are happy around me.

I have built our church on the earth and our naked feet have made the earth hard as we dance.

Akawaio, Guyana

© Eric Lafforgue

We sing with different voices, but we are singing about the same Earth.

Davi Kopenawa Yanomami.

© Mirella Ricciardi

Other galleries

“We, the People” 2020 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International “We...

“We, the People” 2019 - The 50th anniversary Calendar

Our “We, The People” 50th Anniversary Calendar features stunning portraits of...

"We, the People" 2018 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International "We...