Fathers' Day

‘This is my Father’s Father’s Father’s land,’ said a Bushman of his home in Botswana. Yet this ancestral attachment to place means little to outsiders, when there are minerals to mine and trees to fell.

Karapiru, an Awá father, smiles at the camera at his home in Maranhão state, Brazil.

His expression belies the trauma he has endured at the hands of invaders to his ancestral lands. After witnessing the massacre of most of his family by karai, or ‘non-Indians’, Karapiru fled into the rainforest where he remained on the run, in solitude, for ten long years.

When he finally emerged from the rainforest, government officials sent a young man to talk to him. One word instantly transformed Karapiru’s life: the young man said, Father!, for the young translator was Karapiru’s son, who had miraculously survived the brutal attack.

Karapiru has now returned to an Awá village, but his tribe’s problems are far from over. Their forests are disappearing faster than in any other indigenous area in the Brazilian Amazon.

© Survival International

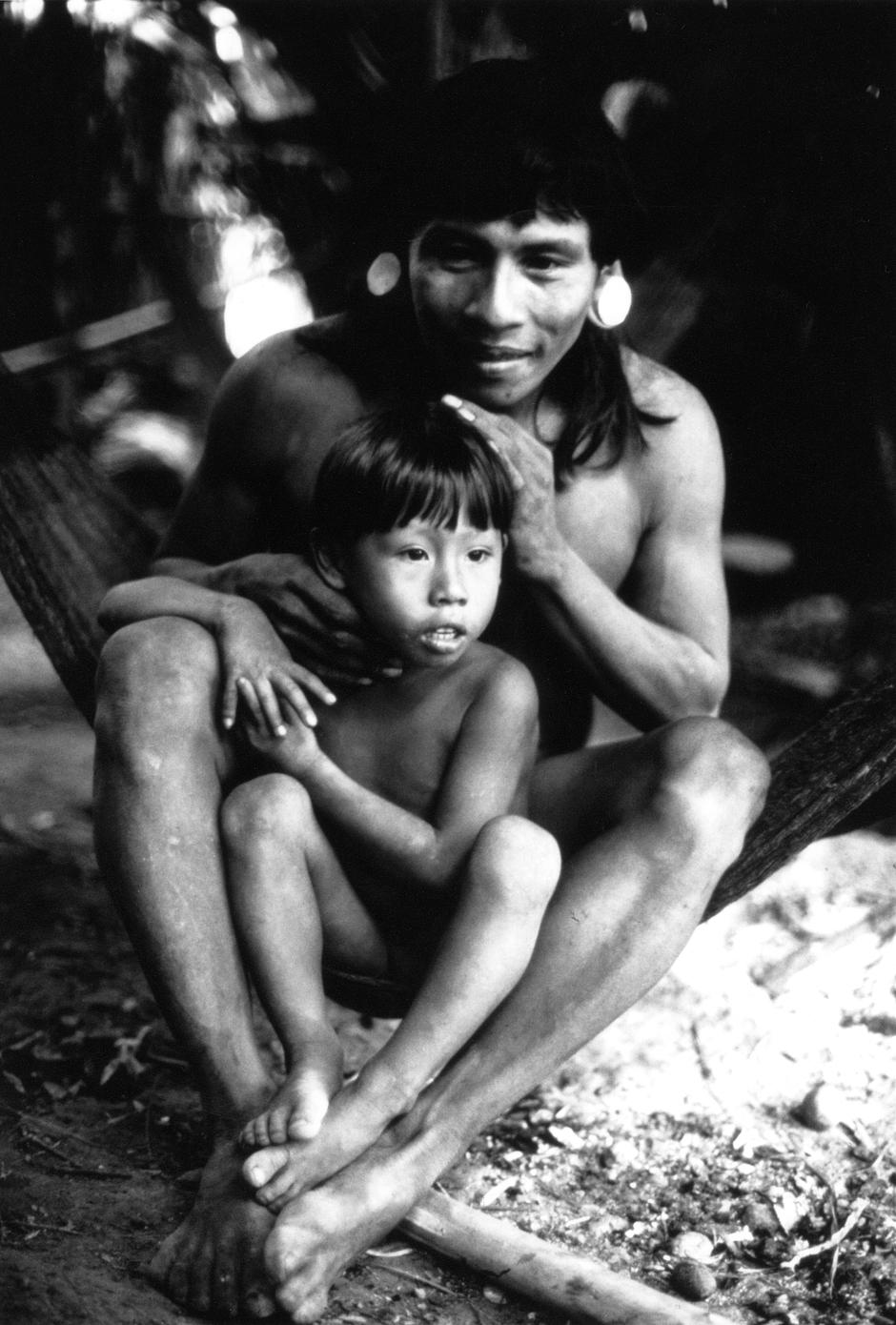

A Yanomami father and child in a hammock made from banana tree fibers.

From the age of five, Yanomami boys accompany their fathers on hunting trips. They learn to shin up trees by tying their feet together with liana vines and practise hunting small birds with bows and arrows.

Sometimes the hunters would also call me at daybreak when they left for the forest, says Davi Kopenawa, a spokesman for the Yanomami people. I went with them and when they killed small game they would give them to me.

That was how I grew up in the forest.

© Victor Englebert/Survival

A Mursi man stands with his cows next to a smouldering fire in the lower valley of the Omo River, Ethiopia. Cattle are the Mursi tribe’s most treasured possessions.

Agro-pastoralist peoples have lived with their cattle along the Lower Omo for several thousand years. Today, however, the Mursi and other tribes’ homeland is threatened by the construction of Gibe III, a massive hydroelectric dam, and by the leasing of vast tracts of tribal land to foreign companies and individuals in order to grow and export biofuels, cotton and food. The dam will block the southern part of the river, so ending the Omo’s natural flood cycle and jeopardizing the tribes’ flood-retreat cultivation methods.

When we had a lot of flood water in the Omo River we were very happy, said a Mursi man.

Now the water is gone and we are all hungry. Please tell the government to give us back the water.

© Kate Eshelby/Survival

A Guarani father leads his family through a sugar cane plantation that was once his forest homeland.

For the Guarani people of Brazil, land is the origin of all life. They once occupied an area of forests and plains totalling 350,000 square kilometers, but violent invasions by ranchers have devastated their territory. Almost all their land has now been stolen.

Today, they are squeezed onto tiny patches of land surrounded by cattle ranches and vast fields of soya and sugar cane. Some have no land at all, and are forced to live in makeshift shacks by busy roadsides.

Laranjeira Nanderu was my father’s land, my grandfather’s land, my great grandfather’s land, a Guarani man told Survival. We need to go back there so we can live in peace. That is our only dream.

© João Ripper/Survival

Father and son Mongemba and Indongo from the Ba’Aka ‘Pygmy’ tribe.

Amongst the Ba’Aka, who live in the Republic of Congo and Central African Republic, fathers spend approximately half the day near their babies. They even offer them a nipple to suck if the child is crying and its mother – or another woman – is not available.

It is not uncommon to wake in the night and hear a father singing to his child, says Professor Barry Hewlett, an American anthropologist who lived with the Ba’Aka for years.

For decades Pygmies have been the victims of landgrabs in the name of conservation, as well suffering from the consequences of mining, logging and palm oil development.

There are currently plans to mine iron ore in the Tridom region of the Congo basin. This will bring in railways and a huge influx of laborers, further destroying the livelihoods of thousands of Baka and Bakola Pygmies.

© Jerome Lewis

Kolu, of the Dongria Kondh tribe, on the lower forested slopes of the Niyamgiri Hills in southern Odisha, India.

The Dongria Kondh call themselves Jharnia, meaning ‘protector of streams’, as they have long been the guardians of the mountains and life-giving rivers that rise within Odisha’s thick forests.

The Dongria Kondh have recently fought mining giant Vedanta Resources, which intended to construct an open-cast mine on their land. The mine would have affected the tribe’s sacred mountain, and with it their way of life and identity as a people.

We don’t want to leave. Our forefathers lived here for generations. I cannot say what will happen when I die, but while I’m alive, Vedanta will not enter this village, a Dongria Kondh father told Survival.

© Jason Taylor/Survival

The Waorani people of the Ecuadorian Amazon are known as The fathers of the jaguar, as their shamans receive help from adopted jaguar ‘sons’, who ensure that forest game is kept close to humans. The Jaguar appears to a shaman in his dreams, revealing that he wants to adopt the man as his father.

Although most Waorani now live in permanent settlements, other groups remain uncontacted in and around Yasuni National Park.

We feel like we are disappearing, Waorani spokesman Ehenguime Enqueri Niwa told Survival. For centuries the Waorani have defended their territories, but now the biggest threats are oil exploration, loggers and miners. What will happen to our children when they’re bigger? Where will they live?

The Waorani were first contacted in the 1950s by American missionaries; Enqueri’s father was one of the first members of his tribe to meet the missionaries.

© John Wright/Survival

The Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountains in northern Colombia form the world’s highest coastal range; the snowy peaks that tower over cloud-forested slopes are sacred to the indigenous Arhuaco people.

The Arhuaco have lived here for centuries; they call themselves the ’Elder Brothers’, and believe that they have a mystical wisdom and understanding which surpasses that of others.

Mamos are the Arhuaco’s spiritual leaders, and are responsible for maintaining the natural order of the world. Training to become a Mamo begins at a young age and continues for around 18 years; a young man is taken high into the mountains where he is taught to meditate on the natural and spirit world.

What I do is interact with Nature, and that is why I dedicate myself to the study of ancient wisdom, said Mamo Zäreymakú. My father used to do the same work: to preserve the balance in Nature, to converse with her. I, as a Mamo, represent all living beings.

© Survival International

A Bushman grandfather.

Today’s Bushman tribes are genetically closer to the ancestors of all of us than anyone else; yet they are also amongst the most victimized peoples in the history of southern Africa. Between 1997 and 2002, many Bushmen were forced from their homes in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR) and taken to eviction camps outside the reserve.

The Bushmen took the Botswana government to court. In 2006, following an international campaign by Survival International, and in a landmark victory for tribal peoples the world over, they won the right to return home.

© Dominick Tyler

Salomon Dunu Uaqui Moconoqui, a Matsés grandfather and plant medicine expert, was one of the first among his people to be contacted by US missionaries in 1969. He wears a necklace made from animal teeth and holds a spear made from peach palm wood.

The Matsés, who are known as the ‘Jaguar people’ of Peru and Brazil, are divided between those who are tsasibo and those who are macubo, terms which refer to how they relate to other humans, spirits and animals. From the moment of conception, a Matsés child’s grouping is determined by that of its father.

Today, the Matsés are in danger of losing their lands to Canadian oil company Pacific Rubiales, which plans to cut hundreds of miles of seismic testing lines through their forest home, and drill exploratory wells.

Our forefathers always told us that outsiders cause conflict, Marcos, a Matsés man, told Survival. Just like the rubber boom, they are coming again to cause conflict amongst us. As indigenous people we need space for our homes and space in which to hunt. I want to confront the oil company, just as our fathers have prepared us to do.

Survival International is leading an international campaign to ensure that Matsés lands are not devastated by Pacific Rubiales, and that their survival as a people is ensured:

http://www.survivalinternational.org/tribes/matses

© Survival International

Other galleries

“We, the People” 2020 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International “We...

“We, the People” 2019 - The 50th anniversary Calendar

Our “We, The People” 50th Anniversary Calendar features stunning portraits of...

"We, the People" 2018 Calendar

Discover a new tribal portrait each month with the Survival International "We...