'There are medicines out there that I know about ...'

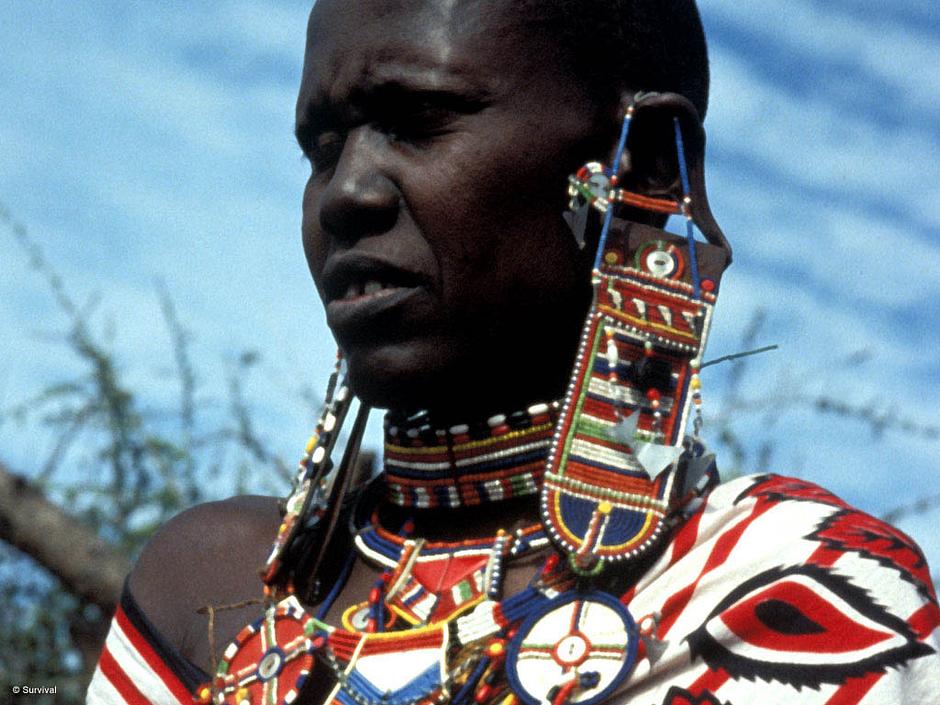

From the Buchu plant as a treatment for kidney disease to bears’ gall bladders to ease wound infections … the medicinal knowledge of tribal peoples.

It was just after dawn in Yaeda Chini, an area of Tanzania that lies to the south of the Serengeti plains. I was walking through bush land with a group of men from the Hadza tribe; they were hunting for warthog in the relative cool of the day.

I was scratched and bleeding from scrambling through spiked acacia trees when a different, searing pain coursed through my arm. A sharp jab, then the frightening flood of a heavy heat that made my hand swell and my stomach heave. And then came the first unwelcome prickle of another sensation: panic. I was carrying no antihistamines.

Gonga, one of the older hunters, immediately searched the bush for the cause of my pain. He pointed to a gossamer-thin, hexagonal-shaped structure hanging from a branch, and spoke in Swahili to our Maasai translator. ‘Wasps’ nest,’ I was told. Grabbing a handful of leaves from another bush, he pressed them to my arm; the cool compress eased the pain.

The hunter-gatherer Hadza people are thought to have lived in Yaeda Chini for up to 40,000 years; for much of this time, they have depended on natural plant-based remedies from the bush to treat illnesses. They are not alone in viewing their homeland as a pharmacy. Today, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that in some Asian and African countries, up to 80% of the population still relies on plants for their primary health care.

Plants have been vital in the development of as many as 50% of today’s prescription drugs. Were it not, in fact, for the specialized botanical knowledge of Indigenous and tribal peoples, particularly those who live in the rainforests, many vital medicinal compounds might still be unknown.

The manufactured painkiller aspirin, for example, was developed from the bark of the white willow tree, which American Indians boiled to treat headaches. The drug Taxol, an extract from the bark and needles of the Pacific yew tree which the American Indians recognized for its immunity-building powers, is now used to treat ovarian and breast tumours.

Thousands of miles away, in South America, plant products that are used as poisons by Indians have become important in western medicine, such as the arrow poison ‘curare.’ ‘Traditionally, it has been used on the tips of arrows to render prey immobile, and has now been appropriated as a muscle relaxant for humans, making possible such procedures as open-heart surgery,’ says Stephen Corry, Director of Survival International, the organization that campaigns for tribal rights. In southern Africa, the Buchu plant, which has long been made into poultices by Bushmen tribes in order to treat small wounds, is known to help kidney and urinary tract diseases (as early as 1821, a London drug firm registered the plant as a remedy).

Despite the fact that more than 50,000 plant species are used worldwide for medicinal purposes – the Shuar of Peru alone use 100 different species solely for stomach ailments – it is believed that the therapeutic value of many others is still unknown to western scientists. Given that the world’s estimated 150 million tribal people have studied the flora of their respective ecosystems for generations in order to survive, it makes common sense to place far greater value on their knowledge and experiences, honed from millennia of trial and error.

In the Amazon rainforest, it would have taken years of experimentation for the Yanomami people to find out that the juice of the woody Cat’s claw vine relieves diarrhea (studies in Europe have also revealed its efficacy in treating rheumatoid arthritis), and that the bark of the Copal tree treats eye infections.

These arcane conclusions demonstrate the time taken to understand local environments. In Canada, the Innu peoples know that earache can be successfully treated with the inner scrapings of beavers’ scrota and wounds prevented from developing infections through the application of a bear’s gall bladder. As an Innu man said, ‘there are medicines out there that I know about. In the country I am an environmentalist and a biologist.’

Within tribal communities this role of ‘biologist’ is often that of shamans, who combine the diagnostic and remedial power of plants with spiritual healing. Many use powerful hallucinogens from bark, leaves, flowers, cacti or mushrooms, to induce altered states of consciousness. Such mind-altered conditions allow shamans to commune with the spirits of natural phenomena and determine the cause of their patients’ illnesses. ‘When for the first time you sniff the powder from the yakoanahi tree,’ says Davi Kopenawa, a Yanomami shaman from Brazil, ‘the xapiripe spirits begin to gather around you. Gradually, they reveal themselves.’

Yali shamans believe that certain plants that grow in the central highlands of West Papua are powerful enough to drive ghosts from villages, rats from fields, ensure the arrival of rain or the success of the hunting trip. ‘One Yali elder taught me about the magic plants of his world,’ says Dr. William Milliken, an ethno-botanist at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, London. ‘So secret and powerful were the plants, he sometimes only whispered their names so as not to speak them aloud.’

Speaking the words aloud, however, has informed the knowledge of generations of shamans. Tribal languages are those of the land, with vocabularies that contain botanical information gathered over centuries. For the Kallawaya, traveling healers in Bolivia, their vast knowledge of wild plants is encoded in a ‘secret’ language called Machaj Juyai and handed down from father to son; their languages are very much their libraries.

Just as valuable, perhaps, as the botanical knowledge of tribal peoples is the holistic approach of many to human wellbeing, which is seen not just as the absence of physical illness, but a maintained state of emotional, physical and spiritual harmony. Man is not an island that thrives independently of nature; people are reliant on a harmonious sense of belonging to each other and to the earth for their health. ‘The environment is not separate from us,’ says Davi Kopenawa, ‘we are inside it and it is inside us.’

It is a philosophy that takes into account the whole person, whereas western medicine has tended to consider an individual as composed of separate parts. As the industrialized world becomes increasingly aware of the adverse physical and mental effects of separation from nature, however – and conversely, the positive effects of engaging with it [one US study has shown that gall bladder surgery patients who have views of nature from their hospital beds need less pain medication than those who have views of a concrete wall] – the need to integrate western medicine with the inductive understandings of tribal peoples becomes ever more logical.

Ironically, just as western medicine rediscovers the therapeutic value of the natural world and man’s place in it, so the world’s rainforests and other ecosystems are being destroyed. It is estimated that loss of habitat and over-harvesting threatens the survival of over 50,000 currently known medicinal plant species.

The plant Hoodia, for example, which has long been know to the Bushmen of southern Africa as an appetite suppressant, has been over-harvested by pharmaceutical companies to create weight-loss medications. ‘Plant extinctions are occurring at a rate unmatched in geological history, leaving ecosystems incomplete and impoverished,’ says Belinda Hawkins of the Botanic Gardens Conservation International. ‘And as we lose species, so we lose vital components necessary to our own survival.’

© Dominick Tyler

© Dominick Tyler

Many of the habitats that are still rich in biodiversity tend to be those that remain under the stewardship of tribal peoples. The Jarawa, for example, inhabit the last remaining tracts of virgin rainforest in the Andaman Islands, and a quick look at a map of the Amazon shows that in many areas outside tribal reserves, deforestation is all but complete, whereas within tribal areas, the forests remain largely intact.

Just as it makes sense for western scientists to consider the botanical discoveries and knowledge of tribal peoples in the ongoing search for naturally curative compounds, so it stands to reason that the best way of protecting such precious plants is to secure the land rights of their Indigenous guardians.

It was time to rest, so I followed the Hadza men as they clambered to the top of a rocky outcrop, from where we had a view over acacia woodland, deep green from the recent rains.

We sat in silence while a cigarette was passed around. My arm had stopped throbbing; I felt well looked after.

Gonga broke the silence. ‘This is my home’, he said, making a sweeping gesture across the land as far as the soda waters of Lake Eyasi. Beyond lay the ramparts of the Great Rift Valley, and the red earth of the Iraqw people. ‘Our grandparents lived here; I am part of the land. Our medicines are here. Without the land, there is no life.’