Noble Savages and Other Myths: What Indigenous People Can Teach Us about Biodiversity

The noted environmentalist, Robert Goodland, was an early torchbearer of the warning that if you cut down a lot of Amazonia, it is destroyed forever. He explained that the rainforest lies on extremely poor soil and grows largely off its own detritus. When very large areas are felled, the trees aren’t able to grow back as they can’t produce the wet and rotting vegetation needed for the forest to regenerate.

When I started working for tribal peoples’ rights nearly fifty years ago, I often referred to Goodland’s work:

“RaceAmazonia, and it’s gone, destroying not only its Indigenous inhabitants but much of the rest of the world besides, because the resultant increase in carbon in the atmosphere would accelerate climate change (as it would eventually come to be called), raise sea levels and drown cities like London, New York and San Francisco”

Goodland was broadly right, but he omitted one aspect of a vital thread in the complex web connecting all life – prehistoric humans. Mysteriously, Amazonia has some zones of rich humus called “dark earth”. Although Western scientists have only started studying it fairly recently, dark earth has been known about for at least a couple of centuries. After the Civil War, it was even cited as enticement for American Confederates to emigrate to Brazil, where slavery was still legal.

Science has now figured out that this highly fertile soil is not a “natural” phenomenon. It was made by people – the result of countless generations of Indigenous women and men discarding food and waste and enriching the soil in other ways. It’s come as a surprise to many that the pre-Columbian inhabitants of Amazonia had such an impact on their environment.

The first European explorers reported seeing cities of thousands and “fine highways” along the rivers they descended. This used to be dismissed as a sixteenth-century invention, but scientists are finally recognising that human habitation of Amazonia was so extensive, starting ten thousand years ago or more and rising to a population of perhaps five or six million. When the Spanish arrived, most areas had been cleared at least once, while leaving the surrounding forest intact and so avoiding Goodland’s total collapse prediction. It wasn’t just along the big rivers either; satellite imagery, backed by traditional archeology, is now revealing extensive prehistoric habitation in the forest interior as well.

It turns out that Amazonia doesn’t match at all with the image Europeans have projected on it in recent centuries. It was never a “wilderness” inhabited only by a few people leaving little impression on the landscape, at least not for thousands of years. On the contrary, the ecosystem has been shaped – actually created – by communities who adapted their surroundings to suit their taste.

These early “Indians” hunted hundreds of animals and birds and doubtless made pets of others. They used thousands of different plants for food, medicine, ritual, religion, hunting and fishing tools and poisons, decoration, clothing, building, and so on. They cultivated some close to their dwellings, and planted others along distant hunting and fishing trails. They spread seeds and cuttings, carrying them from place to place.

They significantly altered the flora, not only by moving plants around – their ancestors, for example, may well have carried the calabash, or bottle gourd, all the way from Africa – but also by changing them through selective breeding. Science has, so far, counted 83 distinct plant species that were altered by people in Amazonia, and the region is now recognised as a major world centre of prehistoric crop domestication.

An easy and obvious way to improve plants is to use only seeds from trees producing the biggest fruits and always to leave someone the tree to reproduce, but other modifications went much further. For example, manioc, the most common foodstuff, barely survives without human intervention. A typical Amazon tribe recognises well over a hundred distinct varieties of this single species (and doesn’t need writing to remember them). Now it’s one of the world’s main staples, sustaining half a billion people throughout the tropics and beyond, yet it produces very few viable seeds. Manioc generally survives and spreads only if people plant its cuttings. Like other fully domesticated plants, it’s a human “invention”.

Europeans brought catastrophe to the Amazon rainforest in the sixteenth century. Within just two or three generations of first contact, probably more than ninety per cent of the Indigenous population was dead from violence and new diseases against which they had no immunity. Proportionally, it was one of the biggest known wipeouts of the last thousand years, though most people have never heard of it. It wasn’t total though: Some Indians survived both the epidemics and the subsequent, and still ongoing, colonial genocide.

Others avoided both disease and killing and retreated away from the big rivers. Well over a hundred such “uncontacted tribes” have survived. Where their land hasn’t been stolen, Amazon Indians – now totaling over a million – are still enjoying their own, human-made environment, and not any invented “wilderness”. They don’t live like their ancestors did (no one does, not even the uncontacted tribes) but many seem to have kept some of the same values.

Research is revealing that practically everywhere you look, the solid ground on our planet has been changed by humans for thousands of years, if not longer. Although this isn’t what is generally taught, it’s really little more than common sense. As in the Amazon Basin, prehistoric people would obviously have favoured food plants with the best yields wherever they could, and would have carried them from place to place. The “pristine” hunter-gatherer who has practically no impact on the environment is as much a myth as any “untrammeled wilderness.”

*

Nowhere is the prehistoric shaping of landscape clearer than in Australia, where the long-accepted narrative is now being turned on its head. Aboriginal people have lived in Australia for at least 65,000 years, or perhaps up to twice as long (which would upset current “out of Africa” theories). They were there well before our species turned up in either the Americas or Europe. Like Amazon Indians, they too have long been described as small bands of “hunter-gatherers” having practically no impact on the “wilderness”.

It turns out that, as in Amazonia, this isn’t true in Australia either. The early British explorers reported seeing vast areas that reminded them of English estates. There were cultivated grasslands, cleared of scrubby undergrowth but scattered with stands of trees giving edible fruits and shade. It’s now thought that some 140 different grasses were harvested. One surveyor noted, “The desert was softened into the agreeable semblance of a hay-field…we found the ricks or hay-cocks extending for miles.” He recorded how the Aboriginal people made “a kind of paste or bread” and grindstones some 30,000 years old have been found. That’s well over twice as old as humankind’s supposed “discovery of agriculture” in Mesopotamia.

The Europeans also reported finding quarries near villages, and towns of numerous stone-built houses. One is reckoned to have provided housing for 10,000 people. They also came across dams, irrigation systems, wells, artificial waterholes – stocked by carrying fish from one to the other – and fish traps, which might well be the first human structures so far found on Earth. One archaeological team thinks they are at least 40,000 years old.

Aboriginal people preserved and stored food, including tubers, grains, fish, game, fruits, caterpillars, insects, and much else. Harvests of both grain and edible insects brought together large congregations, doubtless to trade, to perform ceremonies and rituals, and to forge new liaisons and alliances.

The world’s oldest edge-ground axe found so far comes from Australia and dates back to at least 46,000 years, but irrespective of whether they had such tools or “discovered” agriculture before others, it now seems clear that the Aboriginal people of Australia were changing the landscape at least as much as anyone else around the world.

Just as in Amazonia, the European newcomers quickly destroyed all this. In many areas, their imported sheep destroyed the ground cover within just a few years. Overnight dews became less humid; the earth hardened, less rain was absorbed and so flowed into the rivers which then flooded, washing away topsoil. It was all completely contrary to the settlers’ conviction that they were introducing sensible and productive land use. Rather, the earth’s fertility, which had been carefully husbanded over countless generations, was eroded in a single short human lifespan. The colonists understood nothing of what they found in Australia.

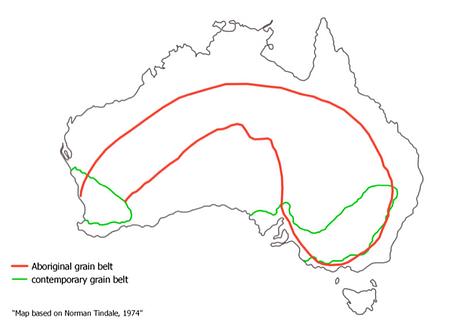

An extraordinary map showing how much of the continent was once covered within the Aboriginal grain belt, as compared to how little is nowadays, should surely feature in every Australian school. It shows the quite extraordinary degree of ecological loss that the attempted destruction of Aboriginal Australia brought in its wake.

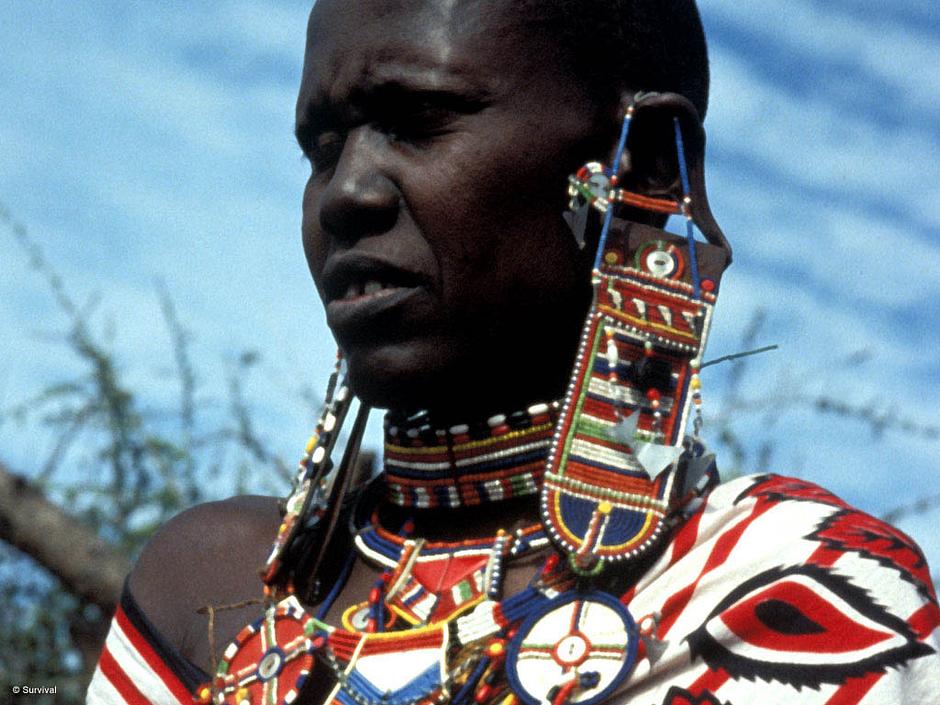

© Survival

© Survival

In some Australian coastal areas, killer whales and dolphins were observed, apparently working in tandem with people. They drove other whales and fish towards the shore where they could be easily harvested, with both people and dolphins taking their share. This astonishing partnership was noted by several early explorers but doesn’t seem to have been recorded elsewhere in the world as far as I know.

It’s certainly likely, however, that our ancestors in many places have long lived in a beneficial symbiosis with animals, including “wild” ones, just as tribal peoples do today. For example, the Hadza in Tanzania have long located honey though a whistled exchange with a species of bird which, though wild, has learned to lead the hunter to the right tree. The man climbs to the hive and smokes out the bees. The groggy insects focus on rescuing enough honey to move elsewhere, and so don’t attack. The hunter collects the honeycomb, while the bird, smaller than a blackbird, waits patiently to claim its share. Both its common and scientific name acknowledges its job – greater honeyguide (indicator indicator).

No one can ever know how long ago this sublime relationship first developed. We are certain, however, that other animals have not only been deliberately moved long distances but also, like plants, turned from one species into another. For example, European ancestors were breeding dogs from wolves at least 15,000 years ago, and likely more than twice that (though today’s dogs don’t seem to be directly descended from the earliest examples so far found).

Dogs extend a human’s hunting range and ability, inevitably altering the balance of predators and so modifying other fauna and flora in turn. It’s simple: If people hunt more wild pigs, say, as a result of having dogs, then more plants which the pigs eat will grow to fruition. This alone will change the flora – though it won’t be noticed by Europeans, who imagine all landscapes are “wild” unless they’re farmed European-style.

Their error is partly rooted in the enduring, though entirely mistaken, belief in the so-called discovery of agriculture. However, much it is repeated as an article of faith. This didn’t take place in the Middle East around 12,000 years ago, and didn’t result in a leap forward in the quality of life. (In fact, it’s now thought that the resultant increase in sedentarism and animal-to-human disease transmission initiated a great increase in human suffering. The fictions first emerged in the early twentieth century at a time when “scientific racism” was widely accepted in Northern Europe and America.

The myths are intertwined: The archeologists saw themselves as descendants of the first agriculturalists, and were convinced they were responsible for the most advanced civilisation on Earth. Europe, they believed, had forged ahead when the other (supposed) “races” lagged behind.

It turns out that the really hurtful fantasy is the invention of this “superior white man” rather than any “noble savage.” The truth is that people were taming, domesticating or moving plants and animals long before the proliferation of grain crops in any imagined “cradle of civilisation.”

April 11, 2019