Modi’s Escalating War Against India’s Forests and Tribal People

The result of the biggest election in history, India 2019, is terrible news for tribal peoples in the world’s biggest democracy. Politicians with authoritarian nationalist inclinations like India’s newly invigorated Narendra Modi are in vogue around the world, and while many minority groups are feeling the impact of this surge to the right, the past year has seen an alarming escalation of the threat against tribal and Indigenous peoples worldwide.

The “Trump of the Tropics”, Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro, has received widespread condemnation for his attack on Indigenous peoples in Brazil, and rightly so. However, the sheer scale of India’s assault on its tribal people is unprecedented: around 8 million people are set to be evicted from their homes, and tens of millions may soon be subject to draconian laws which allow them to be “shot on sight” with essentially no due process or legal recourse.

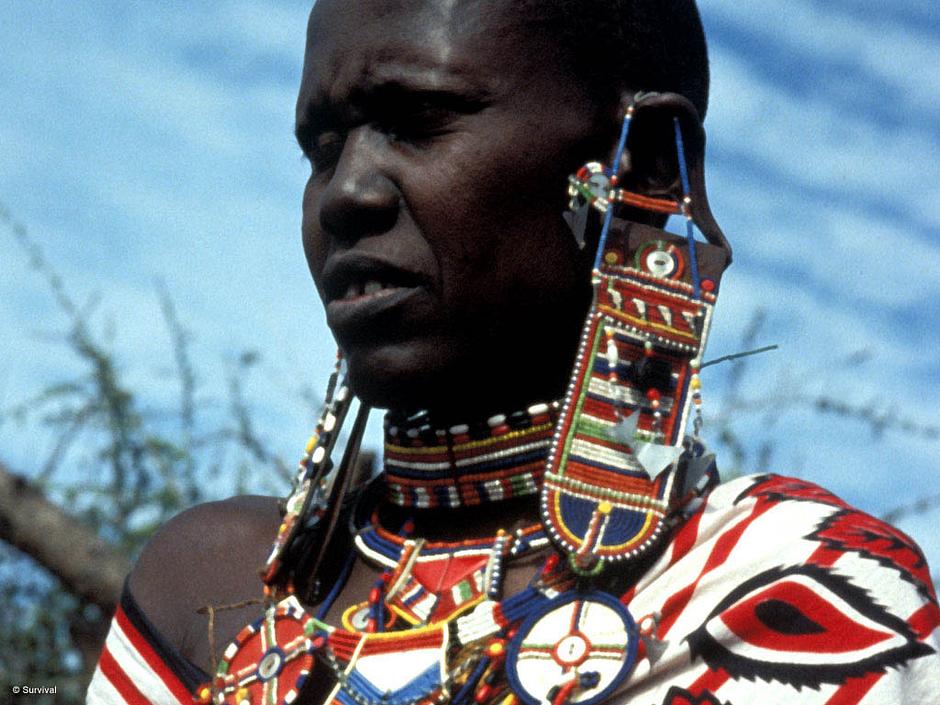

India’s famous forests are the battleground on which Modi’s administration have waged war against the nation’s tribal peoples. Many of India’s tribes live in forests and rely on these ecosystems to survive. These vast tracts are rich in biodiversity and are home to some of the country’s most iconic animals, notably the tiger.

Tribes like the Chenchu, of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh, have always lived harmoniously with the tigers, whom they honour and revere, but do not fear. According to one Chenchu man, Thokola Guruvaiah: “We love [tigers] as we love our children. If a tiger or a leopard kills our cattle, we don’t feel disappointed or angry, instead we feel as if our brothers have visited our homes and they have eaten what they wanted.”

In February 2019, India’s Supreme Court ordered the eviction of around 8 million people from India’s forests following a petition by conservation groups, who claim that human presence in the forests poses a threat to wildlife (though once the inhabitants have been evicted, these same conservationists tend to take no issue with hordes of tourists colonising the land in loud, polluting four wheel drives.) This perceived (but entirely false) threat that tribal people pose to wildlife has already led to 100,000 people being evicted from their ancestral homelands. Though these families and communities should be compensated, all too often the promised benefits don’t materialize.

The results of such evictions are devastating, and people who were never in poverty, thanks to the bounty of the forest, are then needlessly forced into destitution. Anyone callous enough to say that this suffering is a price worth paying for tiger conservation should note one important fact: in the first tiger reserve in India where tribal people won the right to stay permanently on the land, tiger numbers increased by over three times the national average.

As their rights are being systematically eroded, more and more evidence shows that tribal people are the best conservationists and guardians of the natural world. These communities have made their living as hunter-gatherers or subsistence farmers for generations, so their day-to-day survival has always depended on their profound understanding of their environment and ability to maintain healthy wildlife populations: 80% of the planet’s biodiversity is in tribal territories. They possess unique insight and expertise that is proving invaluable to science and conservation and will prove essential in the urgent fight against climate breakdown.

Eight million evictees is more people than the population of New York or London. Where will they go? How will they survive once they are cut off from the resources they depend on, but have no money or means to obtain elsewhere? Appallingly, it was wilful dereliction of duty from the government that led to this clear miscarriage of justice: there was no-one to put the argument against the eviction motion because the government didn’t bother to send a lawyer to court to defend their own law. Following widespread criticism and protests the government was forced to intervene, and the Supreme Court stayed their ruling until July. Following the election result there will be less pressure on the government to act, so when the court reconvenes, it seems likely that the ruling, in some form or other, will be upheld.

If so, the now poor and desperate evictees may well be shot should they attempt to re-enter the forest to gather food, firewood or medicinal plants. This is according to the government’s proposed amendments to the Indian Forest Act, 1927 (IFA), which were leaked in March this year. Although this legislation was created initially by the British to establish legal control over India’s forests, the new proposals are, remarkably, even more draconian than the original colonial law.

Forest officials, “justified” by “conservation,” will have a startling level of impunity, including the power to shoot people virtually without redress, enforce “communal punishments” against an individual’s entire village, and suspects will be presumed guilty and treated like criminals until they can prove their own innocence.

Under the proposals, no forest officer can be arrested for any offence committed in ‘discharge of his official duties’ without an investigation, and state governments can’t sanction an inquiry into wrongdoing without constituting an inquiry under an executive magistrate. Where similar policies have been in force, it’s led to “shoot first, ask questions later,” and the results have been catastrophic.

At Kaziranga National Park in Assam, for instance, where staff were told “never allow any unauthorized entry – kill the unwanted,” 65 people were killed between 2010 and 2016 alone. In 2016, a seven year old boy was shot and suffered life-changing injuries. While the law is supposed to prevent poaching, Survival International has revealed that in fact innocent people have been killed by rangers, including a man with learning difficulties looking for a lost cow.

Out of the estimated 370 million Indigenous people worldwide, over 100 million live in India, meaning the country is home to over a quarter of the world’s Indigenous population. Though Indigenous rights are of grave concern around the globe, the sheer scale of what’s happening in India is unparalleled: the number of individuals, families, and communities who are poised to have their lives utterly destroyed is mind-bendingly huge.

As a Chenchu man told one of my colleagues recently: “Without us the forest won’t survive, and without the forest we won’t survive. Staying in a town, even for a couple of days, is a nightmare for us. If you are asking us to live there forever then we are sure to die. Nobody has the right to send us out of this forest, and if you are doing that then indirectly you are asking us to die.”

Jonathan Mazower works for Survival International.

MAY 31, 2019