‘We were made the same as the sand’

© Dominick Tyler

© Dominick TylerThis photo-essay follows the Botswana Bushmen’s forced eviction from their ancestral homeland in 2006.

The Bushmen are the Indigenous peoples of southern Africa. Largely hunter-gatherers, they have lived in the region for 70,000 years, or more.

Today’s Bushman tribes are genetically closer to the ancestors of all of us than anyone else; yet they are also the most victimized peoples in the history of southern Africa.

In 1961, The Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR) was created to protect the ancestral lands of the 5,000 Gana, Gwi and Tsila Bushmen.

© Dominick Tyler

© Dominick Tyler

However, their reserve, a vast area bigger than Switzerland (52, 000 km2) of open plains, grasslands and fossil rivers, lies in the middle of the richest diamond-producing area in the world. After diamonds were discovered in the CKGR in the 1980s, the Botswana government forcibly evicted the country’s oldest inhabitants.

Between 1997 and 2002, almost all Bushmen were forced from their homes and taken away from their hunting grounds to eviction camps outside the reserve. Their villages were pulled down, the well they had used destroyed, its water drained into the sand. The government tried to make what are their human rights – home, food and water – impossibilities.

The Bushmen took the Botswana government to court. In 2006, in a landmark victory for tribal peoples the world over, they won the right to return home.

Liquid error: internal

The government continued to prevent the Bushmen from returning home, by banning them from accessing a well which it capped during the evictions.

With support from Survival International, the Bushmen appealed a 2010 High Court judgment that enforced the ban.

On 27th January 2011, in a victory for the Bushman peoples and human rights worldwide, the Botswana’s Court of Appeal quashed the 2010 judgment.

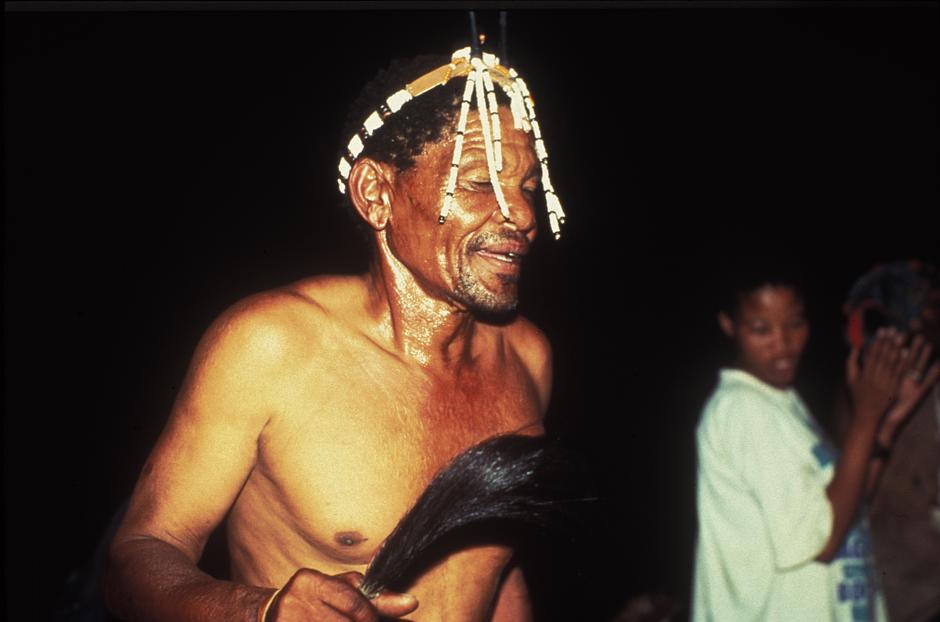

In 2006, the acclaimed photo-journalist Dominick Tyler spent time in New Xade, one of the eviction camps, and was with a convoy of Bushmen when they journeyed home to the CKGR.

These are his photographs.

© Dominick Tyler

© Dominick Tyler

During the forced evictions, their traditional homes were pulled down, their school and health posts closed, the well they had used destroyed, and the water drained into the sand.

‘If I went to a Minister and said, ‘move from your land,’ he’d think I was mad,’ said a Bushman.

Yet this is what happened to the peoples who once lived from the Zambezi Basin to the Cape.

The Botswana government claim that the Bushmen need to leave behind what they assert is a miserable life ‘among the animals,’ in order to ‘catch up’ with the development of the rest of the country. They have also argued that the Bushmen’s presence in the reserve is not compatible with preserving wildlife.

‘They should be elevated from the status where they find themselves,’ said the Foreign Minister of Botswana. ‘We would all be concerned that any tribe should remain in the bush communing with flora and fauna.’

Botswana’s former President, Festus Mogae, asked, ‘How can you have a stone-age creature continue to exist in the age of computers?’

© Dominick Tyler

© Dominick Tyler

In three big clearances in 1997, 2002 and 2005, almost all the Bushmen were forced out of the CKGR, in violation of Botswana’s own constitution.

The government tried to persuade them that the eviction was for the Bushmen’s own good; that they would benefit from the move socially and economically. The provision of education and health services in the new camps were emphasised.

‘How can anyone argue that it’s better to live in the wilderness with animals than be here at the relocation site?’ asked James Kilo, a government representative.

The truth is that the ‘relocation sites’, however, are places of depression, prostitution where AIDS and alcoholism are rife. They are referred to as ‘places of death’ by the Bushmen.

The truth is that forcibly wrenching people away from their lands, homes, myths, rituals and memories is a fast route to the annihilation of self-worth and the breakdown of an entire society.

‘The lion and I are brothers, and I am confused that I should have to leave this place and that the lion can stay,’ said a Gwi leader.

© Dominick Tyler

© Dominick Tyler

Life in the eviction camps means the Bushmen are rarely able to earn their livelihood in the way they have for millennia, by hunting animals and gathering bush plants. Hunting is what they have always known; it is their livelihood, their history and their identity as a people.

Now they have been denied hunting licences, and are frequently arrested and beaten when they do hunt. One Bushman man was given a permit to enter the reserve for three days only; he was followed everywhere by armed guards. Others have have been severely tortured by wildlife officials on suspicion of hunting.

‘The Bushmen are a hunting people,’ said Roy Sesana. ‘I grew up a hunter. All our boys and men were hunters.’

In the eviction camps, however, they are dependent on government hand-outs.

‘I do not want this life,’ says a Gana Bushman. ‘First they make us destitute by taking away our way of life, then they say we are nothing because we are destitute.’

© Dominick Tyler

© Dominick Tyler

The case became the longest and most expensive in the country’s history, despite being brought about by its poorest inhabitants.

A historic victory was theirs in 2006. The Bushmen won the right to return to their lands, the judges ruling that their eviction by the government was ‘unlawful and unconstitutional’.

The first convoy of Bushmen leaving New Xade in an attempt to return to the CKGR is held at the gate to the reserve by game wardens.

© Dominick Tyler

© Dominick Tyler

© Dominick Tyler

© Dominick Tyler

‘We were made the same as the sand, we were born here,’ he says. ‘This place is my father’s father’s father’s land.’

© Dominick Tyler

© Dominick Tyler

One of the ways the government tried to make their home-coming impossible, was by banning them from accessing a water borehole inside the reserve. As rainfall patterns are unpredictable in the CKGR, a borehole is their main source of water.

In June 2010, the Bushmen launched further litigation against the government in a bid to gain access to their borehole.

In the court hearing, the judge ruled that the Bushmen were not entitled to access an existing water borehole on their lands, nor drill a new one, and that they had ‘brought upon themselves any discomfort they may endure.’

At the end of January, however, the judge’s ruling was overturned by a unanimous decision of five Appeal Court judges, who ruled that denying Bushmen access to their well amounted to ‘degrading’ treatment, contrary to the country’s Constitution.

© Dominick Tyler

© Dominick Tyler

Traditionally, the Bushmen find water in ‘pans’ – rain-filled depressions in the sand – and from plants such as tsamma melons and roots, techniques learned over thousands of years of surviving in the desert during the dry seasons, when the water holes of the Kalahari sand-face turn to dust.

‘You learn what the land tells you,’ says Gana Bushman Roy Sesana.

When the ‘pans’ are empty, life without access to a borehole in one of the driest places on earth becomes extremely difficult.

In their historic decision, the Appeal Judges found that the Bushmen have the right not only to use their old borehole, but to sink new boreholes.

They also found that the government must pay the Bushmen’s costs in bringing the appeal.

© Dominick Tyler

© Dominick Tyler

‘We have been waiting a long time for this,’ said a Bushman spokesman. ‘Like any human beings, we need water to live.’

‘Why must I move?’ asked a Bushman. ‘Why is the government of Botswana persecuting the Bushmen?’

‘I was born in this place and I have been here for a very long time. This is my birthright: here, where my father’s body lies in the sand.’