The best conservationists made our environment and can save it

by Stephen Corry

This is the seventh article in former Director Stephen Corry’s series on conservation. For a full list of all articles, please click here. Versions of the articles below were published by The Elephant on April 11, April 19, and April 25, 2019.

Part 1: Our handmade world

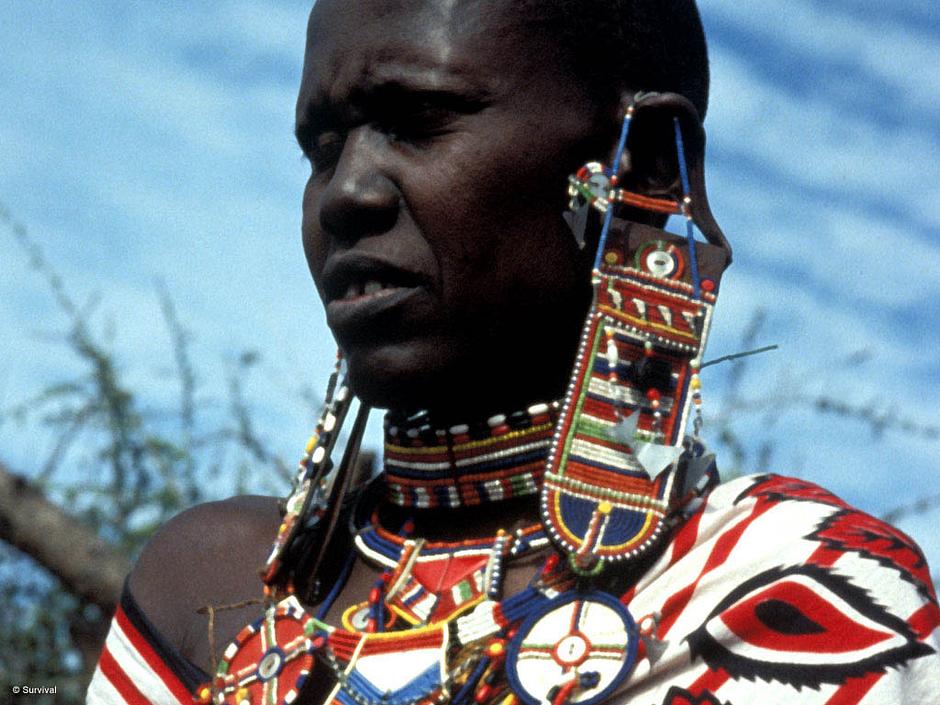

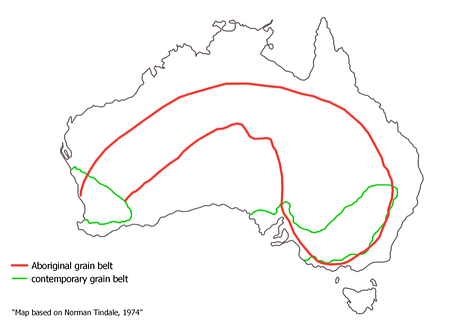

The prehistoric environment was created by humans who enhanced biodiversity, altering the plants and animals to suit themselves. Contemporary tribal peoples are still doing this today. The fact that they are the world’s best conservationists is not a “noble savage” romantic fantasy, it can now be proven. Yet the conservation industry is destroying these peoples and forcing them out of the territories they made and could save. Stephen Corry argues that if we stop this, everyone will benefit, along with the environment. bq. “If we were to leave this jungle, then it would be difficult for it to survive. There is forest and water because we are here. If we were to leave, then come back in a while and look, there will be nothing left.” – Baiga tribesman, India The noted environmentalist, Robert Goodland, was an early torch-bearer of the warning that if you cut down a lot of Amazonia, it’s destroyed forever. He explained that the rainforest lies on extremely poor soil and grows largely off its own detritus. When very large areas are felled, the trees aren’t able to grow back, as they can’t produce the wet and rotting vegetation needed for the forest to regenerate. When I started working for tribal peoples’ rights nearly fifty years ago, I referred often to Goodland’s work: Raze Amazonia, and it’s gone, destroying not only its Indigenous inhabitants but much of the rest of the world besides, because the resultant increase in carbon in the atmosphere would accelerate climate change (as it would eventually come to be called), raise sea levels and drown cities like London, New York and San Francisco. Goodland was broadly right, but he omitted one aspect of a vital thread in the complex web connecting all life – prehistoric humans. Mysteriously, Amazonia has some zones of rich humus, called “dark earth.” Although Western scientists have only started studying it fairly recently, dark earth has been known about for at least a couple of centuries. After the Civil War, it was even cited as enticement for American Confederates to emigrate to Brazil, where slavery was still legal. Science has now figured out that this highly fertile soil is not a “natural” phenomenon. It was made by people – the result of countless generations of Indigenous women and men discarding food and waste and enriching the soil in other ways. It’s come as a surprise to many that the pre-Columbian inhabitants of Amazonia had such an impact on their environment, but it really shouldn’t have: The first European explorers reported seeing cities of thousands and “fine highways” along the rivers they descended. This used to be dismissed as sixteenth century invention, but scientists are finally recognizing that human habitation of Amazonia was so extensive, starting ten thousand years ago or more and rising to a population of perhaps five or six million when the Spanish arrived, that most areas have been cleared at least once – while leaving the surrounding forest intact and so avoiding Goodland’s total collapse prediction. It wasn’t just along the big rivers either: Satellite imagery, backed up by traditional archeology, is now revealing extensive prehistoric habitation in the forest interior as well. It turns out that Amazonia doesn’t match at all with the image Europeans have projected on it in recent centuries. It was never a “wilderness” inhabited only by a few people leaving little impression on the landscape, at least not for thousands of years. On the contrary, the ecosystem has been shaped – actually created – by communities who adapted their surroundings to suit their taste. These early “Indians” hunted hundreds of animals and birds and doubtless made pets of others. They used thousands of different plants for food, medicine, ritual, religion, hunting and fishing tools and poisons, decoration, clothing, building, and so on. They cultivated some close to their dwellings, and planted others along distant hunting and fishing trails. They spread seeds and cuttings, carrying them from place to place. They significantly altered the flora, not only by moving plants around – their ancestors, for example, may well have carried the calabash, or bottle gourd, all the way from Africa – but also by changing them through selective breeding. Science has, so far, counted 83 distinct plant species that were altered by people in Amazonia, and the region is now recognized as a major world center of prehistoric crop domestication. An easy and obvious way to improve plants is to use only seeds from trees producing the biggest fruits and always to leave some on the tree to reproduce, but other modifications went much further. For example, manioc, the most common foodstuff, barely survives without human intervention. A typical Amazon tribe recognizes well over a hundred distinct varieties of this single species (and doesn’t need writing to remember them). Now it’s one of the world’s main staples, sustaining half a billion people throughout the tropics and beyond, yet it produces very few viable seeds: Manioc generally survives and spreads only if people plant its cuttings. Like other fully domesticated plants, it’s a human “invention.” Europeans brought catastrophe to the Amazon rainforest in the sixteenth century. Within just two or three generations of first contact probably more than ninety per cent of the Indigenous population were dead from violence and new diseases to which they had no immunity. Proportionally, it was one of the biggest known wipeouts of the last thousand years, though most people have never heard of it. It wasn’t total though: Some Indians survived both the epidemics and the subsequent, and still ongoing, colonial genocide. Others avoided both disease and killing and retreated away from the big rivers, and well over a hundred such “uncontacted tribes” have survived. Where their land hasn’t been stolen, Amazon Indians – now totaling over a million – are still enjoying their own, human-made environment, and not any invented “wilderness.” They don’t live like their ancestors did – no one does, including the uncontacted tribes – but many seem to have kept some of the same values. Research is revealing that practically everywhere you look the solid ground on our planet has been changed by humans for thousands of years, if not longer. Although this isn’t what is generally taught, it’s really little more than common sense. As in the Amazon Basin, prehistoric people would obviously have favored food plants with the best yields wherever they could, and would have carried them from place to place. The “pristine” hunter-gatherer who has practically no impact on the environment is as much a myth as any “untrammeled wilderness.” Nowhere is the prehistoric shaping of landscape clearer than in Australia, where the long-accepted narrative is now being turned on its head. Aboriginal peoples have lived in Australia for at least 65,000 years, or perhaps up to twice as long (which would upset current “out of Africa” theories). They were there well before our species turned up in either the Americas or Europe. Like Amazon Indians, they too have long been described as small bands of “hunter-gatherers” having practically no impact on the “wilderness.” It turns out that, as in Amazonia, this isn’t true in Australia either. The early British explorers reported seeing vast areas which reminded them of English estates. There were cultivated grasslands, cleared of scrubby undergrowth but scattered with stands of trees giving edible fruits and shade. It’s now thought that some 140 different grasses were harvested, and one surveyor noted, “The desert was softened into the agreeable semblance of a hay-field… we found the ricks or hay-cocks extending for miles.” He recorded how the Aboriginal people made “a kind of paste or bread,” and grindstones some 30,000 years old have been found. That’s well over twice as old as humankind’s supposed “discovery of agriculture” in Mesopotamia. The Europeans also reported finding quarries near villages, and towns of numerous stone-built houses. One is reckoned to have provided housing for 10,000 people. They also came across dams, irrigation systems, wells, artificial waterholes – stocked by carrying fish from one to the other – and fish traps, which might well be the first human structures so far found on Earth. One archaeological team thinks they are at least 40,000 years old. Aboriginal people preserved and stored food, including tubers, grains, fish, game, fruits, caterpillars, insects, and much else. Harvests of both grain and edible insects brought together large congregations, doubtless to trade, to perform ceremonies and rituals, and to forge new liaisons and alliances. The world’s oldest edge-ground axe found so far comes from Australia and dates to at least 46,000 years ago, but irrespective of whether they had such tools or “discovered” agriculture before others, it now seems clear that the Aboriginal peoples of Australia were changing the landscape at least as much as anyone else around the world. Just as in Amazonia, all this was quickly destroyed by the European newcomers. In many areas, their imported sheep destroyed the ground cover within just a few years. Overnight dews became less humid, the earth hardened, less rain was absorbed and so flowed into the rivers which then flooded, washing away topsoil. It was all completely contrary to the settlers’ conviction that they were introducing sensible and productive land use. Rather, the earth’s fertility which had been carefully husbanded over countless generations was eroded in a single short human lifespan. The colonists understood nothing of what they found in Australia. An extraordinary map showing how much of the continent was once covered within the Aboriginal grain belt, as compared to how little is nowadays, should surely feature in every Australian school. It shows the quite extraordinary degree of ecological loss which the attempted destruction of Aboriginal Australia brought in its wake.  © Survival

© Survival

Part 2: Firing up humanity

Our human ancestors were using stone tools well before Homo sapiens evolved three hundred thousand or more years ago. Tools have been found dating back three million years, no less than ten times older than our species. Considering that some birds and fish use – and even fashion – tools (watch crows making hooks), and that any implements made of wood or other organic material will not show in early fossil records, it would be astonishing if our hominid ancestors weren’t using them well before the earliest stone ones we’ve so far found. The most important tool of all was fire. Like much in archaeology nowadays, where microscopic analysis is changing earlier guesswork, the first known date for cooking is being pushed ever further into our deepest past. It’s hotly debated, but some now put it at around a million years ago. Again, that’s long before our species evolved – though of course some of those earlier, now extinct, hominid species are our direct ancestors. Many scientists believe that our very evolution could never have happened without cooking. It massively enhanced our calorie and nutrient intake, so enabling our teeth and guts to grow smaller and our brains, which need huge amounts of energy, to grow much bigger. Brain size is a tradeoff between enabling women to walk upright (a wider pelvis needed to have even bigger-headed babies would make that impossible), and the inordinately large number of years we have to care for our helpless young, longer than any other species. That both engendered and depended on our enormous capacity for social cohesion, empathy and self-sacrifice. In brief, we made fire and cooked our food and that turned us into people, generally more virtuous than vicious – in spite of our striking inhumanities, and the religious dogmatists and “evolutionary psychologists” preaching otherwise. In the ancient Greek myth, Prometheus creates men but can’t endow them with any real strengths – all those have already been given to the animals – so he hands them fire, stolen from the gods, so they can thrive. It sounds about right. This all started happening hundreds of thousands of years ago. Fire, manipulated by our ancestors, changed the world, and cooking was just one part: Regular undergrowth burning had the other really big impact. It’s enormously beneficial: It prevents scorching wildfire conflagrations (look at California or Australia today), and also massively increases biodiversity, however counter-intuitive that may sound to urbanites. It enriches the soil, encourages fresh plant growth, enables wind-blown seeds to germinate in the nutrient-rich ash rather than wither in the undergrowth, and so favors some species over others. All this attracts herbivores, which are followed by predators. When the incoming British colonists in the early twentieth century forbade the Martu Aboriginal people’s custom of controlled burning, the number of kangaroos and lizards in their part of the Australian Western Desert shrank. Aboriginal burning was far from destructive as the Europeans thought: It actually enhanced biodiversity and the food supply. Several key principles have been noted for Aboriginal burning. Neighbors were always forewarned and agricultural lands were fired in rotation at specific times of year when the bush was in the right state and the weather favorable. This limited the fire’s intensity, allowed animals to move out of the way, avoided particular growing seasons, and stimulated particular seeds to germinate under the resulting hot ash. Needless to say, the British banned the practice in many parts of its empire, teaching that undergrowth firing was a destructive and primitive local custom. Some scientists remain schooled in such colonialist prejudice today; the ban on undergrowth burning is still in force in much of India, and is still damaging the environment. Soliga tribespeople, for example, say that the recent massive rise in forest fires in Karnataka wouldn’t have happened if they had been advising on forest management and allowed to continue their traditional burning. People deliberately start fires in many environments and have done so for a very long time. For example, there’s evidence that it’s gone on in Southeast Asia for at least forty-five thousand years. Today, the Xavante in Brazil take careful note of wind and rain before setting their ceremonial fires to assist hunting. The fires remain low and not overly hot because they’re lit so regularly that undergrowth isn’t allowed to grow up year after year. Fire-resistant plants can easily regenerate, and animals have plenty of time to move away. Fire can obviously be destructive, but that includes getting rid of species no one wants, such as deadly disease-bearing insects like the tsetse fly in Africa and the Loranthus tree-killing parasite in India. It also brings new plants and animals in its wake. Regular burning is key in the various “slash-and-burn” methods of farming tropical forests. It’s also called “swidden,” but journalists unfortunately favor the more dramatic name, which has become pejorative. Whatever one calls it, the practice is still widely denigrated and even criminalized by some conservationists, who couldn’t be more wrong. Other scientists, sticking to the evidence, now see it as, “an integral part of many, if not most, tropical forest landscapes that are crucial to biodiversity conservation in all the remaining large tropical forests: Amazonia, Borneo, Central Africa.” The Hanunoo people in the Philippines grow over 280 types of food with swidden, and an even greater variety can be found elsewhere. If undergrowth burning led to cooking, which seems logical, then it dates back over a million years. Considering that some birds not only make tools, but also actually manipulate bushfires by dropping burning twigs to help their hunting – something Australian Aboriginal people have long known – then it’s likely that our ancestors were changing the world with fire more than a million years ago. Science is unlikely ever to be precise about the timing, but that doesn’t alter the fact that the ancient world has long been shaped by women and men. Human-made clearings, whether opened up with fire, axe, or both, modified the local fauna by changing animals’ food and distribution. There’s evidence from the Biligiri Rangaswamy Temple reserve in India that tiger numbers increase in areas where tribal people still live – if, that is, they’re not threatened with eviction and so retain an incentive to maintain their environment. When the people move their fields to leave some dormant, they also abandon the ponds they made for drinking water. The clearings, remnant crops and water attract boar, deer, and other creatures. The big cats then thrive on the easy hunting found in the open spaces. When tribes are evicted “for tiger conservation” the authorities know they have to keep similar clearings open. As a Baiga man told Survival International, “If you remove us, the tiger will disappear as well.” An increase in tiger numbers clearly impacts the cats’ prey. Deer are less plentiful, but they’re healthier than they would be were they never hunted: Sick animals soon become tigers’ lunch. The smaller deer population in turn brings more tree growth which encourages different insect and bird life, and so on and on. It’s all a shifting, interconnected balance that has included human beings as a key environmental shaper for many thousands of years.

When scientists asked them about beluga whale loss in the Arctic, the Inuit explained that warmer temperatures had brought an increase in the beaver population. The beavers took more of the fish, which the whales depended on, and so whale numbers had diminished. It simply hadn’t occurred to the whale experts to include beavers in their research, but the Inuit had observed and interpreted these connections as and when they were developing. Western science has only begun to describe the depth and complexity of such associations over recent centuries, but other “non-scientific” ways of looking at our surroundings have been articulating it for a very long time. Among the best known is the Australian Aboriginal Dreamtime in which every geographical feature, every river, rock, plant, animal, even celestial bodies, and of course all the different tribes of humans, are descended from ancestors who emerged from the earth, and travelled around it in a series of adventures which are remembered and reenacted – and actively “re-created” through such reenactment – today. They capture an essential view of the world and our place in it which science seems to have largely bypassed in making its own invaluable discoveries. Everything really is connected but, needless to say, the Dreamtime version was derided as primitive superstition by the European invaders who brought very different priorities from the British Isles. As well as massacring the native people, they infamously imported rabbits to shoot for sport. The creature immediately spread faster than any other mammal monitored anywhere and is now thought to have caused more species loss than anything else throughout the continent. In brief, humans have been an integral part of the jigsaw of the planet’s ecosystem for thousands, even millions, of years. It’s true we did eliminate some species, including the huge and dangerous auroch, bred by our ancestors into docile domestic cattle. However, prior to industrialization it seems to be the case that we enhanced biodiversity rather than reduced it, at least in many places. Moreover, humans are much more than just a small player in the constantly shifting picture of life on Earth. Together with atmospheric change, we’ve been one of the controlling hands of nature for a very long time, including – and this is a vital point – when our population was far smaller than it is today. Whether it fits in with one’s beliefs or not, humans have always been changing the environment, for better or for worse. The worse part is obvious, and is not of course confined to rabbits destroying Australian biodiversity. Massive urbanization and industrialization have made life easier for some over recent centuries, but have also created rampant environmental degradation, with escalating – in some cases permanent – damage to the health of significant flora and fauna, including humans. There is no shortage of warnings, studies, and prophets sounding that alarm. We can only pray it starts being properly heeded. But what of the other side, how have people since antiquity made the world “better?” I’ve described (above) the increased biodiversity, and that tigers seem to prefer it when they are around tribal people; it turns out that forest elephants do too. Baka “Pygmies” in the Congo Basin, for example, are characterized as “hunter-gatherers” but they also spread food plants around the forest, which attract animals. That’s not just good for elephants: abandoned camps, fertilized with ash and waste, make good habitat for primates. In the Salonga National Park researchers think there may be up to five times more bonobo where the Iyaelima tribe live than where they don’t. The people were unusually allowed to remain inside the park because they too were classified as “wildlife”! Reverence for elephants is widespread in Africa. The Baka, for example, think they have an intimate spiritual connection with the animals – which includes sustainably hunting them for food and ritual. This can seem anathema to those urban Europeans and North Americans for whom wild animals (big ones at least), are anthropomorphized and considered nicer than us, untrammeled by our supposedly unique sin and guilt. If anyone doubts the level of misanthropy to which such “Disneyfication” of nature can sink, they might read the comments accompanying internet stories about poaching. Extremist animal rights advocates repeatedly put animal life far above that of their fellow humans, particularly when the victims are African or Asian. Unfortunately, this often goes unchallenged by those moderates who also value people. Extrajudicial killing, so-called “shoot on sight” is routinely applauded, even if some of the wounded and dead “poachers” include children, and were never criminals but simply poor people looking for food or even firewood or medicinal plants on what was once their land. Those accepting this as mere “collateral damage” in a righteous war against poaching are rejecting human rights, often gleefully.

Part 3: Elephants and the best conservationists

Because humans are elephants’ only serious predator, the creatures must be controlled if the herds are to remain healthy, however unsavory that may sound to animal lovers and however much the public face of conservation hides it. An elephant consumes about 350 pounds of vegetation daily (the average American human takes over two and a half years to eat that weight of potatoes). Like many other plant-eaters, if left unchecked elephants will destroy their own environment. They kill the trees, especially the larger and older canopy cover on which many other species depend. When tribal hunters, like the Waliangulu, and others (pejoratively) known as “Dorobo,” were thrown out and largely eradicated by European colonists stealing their land for game parks in East Africa, savannah elephant numbers grew rapidly to the point where they began destroying the ecosystem. Massive culls had to be arranged by conservationists – and kept quiet from their donors. In one park in South Africa, for example, nearly 600 elephants on average were culled every year from 1967 to 1996. In eastern Kenya, a few hundred tribal hunters had kept the huge herds largely in check, killing perhaps up to 1,500 elephants annually, but after they were banned, subjected to a war on “poaching” and other restraints designed to promote tourism, the herds grew to the point where tens of thousands died of starvation when drought periods arrived. Conservationists are now divided between those who think other methods, such as contraception, should replace culling and those who believe killing remains the only practical solution. What is certain is that there are some areas in Africa today where there are too many elephants for the environment to support. This is in spite of the effects of real poaching which has brought forest (though not savannah) elephants to critically low numbers. African elephant poaching in general – as professional conservationists well know – is largely facilitated by money-grabbing officials, who remain untouched by the current militarization and extreme violence of “fortress conservation.” More than fifty years of public harangues for money to stop the magnificent creature’s supposed “extinction” continue to divert attention away from the real criminals. Aside from humans, there are in fact few creatures which have a bigger environmental impact than elephants which, without controls, double their numbers on average every ten or eleven years. One might speculate how tourists in the Chobe National Park in Botswana, for example, would react on learning that the vast elephant herds they were paying equally vast sums to see were actually environmental wreckers, destroying the “Wild Africa” of Western myth. They are now reckoned to number no less than seven times the land’s capacity. Tribal elephant hunters, like the Baka “Pygmies” in the Congo Basin, are not only good for biodiversity, they were once vital for the health of elephants and they could still be key in stopping their poaching by outsiders. Tribal hunting more widely is internally controlled, largely through the idea that spiritual or physical retribution will fall on any who transgress accepted etiquette. The unwritten rules often include: accepting some delicate zones, such as river headwaters, to be strictly off-limits; not killing female or young animals, or during mating seasons; not hunting near water holes which would frighten animals into not drinking; not killing when game numbers are depleted; and, broadly and simply, not taking more than is needed. It’s not only tribal hunters who bring a positive environmental impact. The U.N.’s Environment Program calls Maasai pastoralists “low-cost guardians,” and reports that their eviction – by conservationists – from the Ngorongoro Conservation Area in Tanzania led to “an increase of poaching and the subsequent near extinction of the rhinoceros population.” Although it seems obvious to many that tribal peoples are the best conservationists, when I was a youthful volunteer for tribal peoples’ rights and was passing on Robert Goodland’s warnings about climate change, I was careful to downplay this notion. The slightest nod in that direction would be met by jeers and sneers, not only from environmentalists but also from some anthropologists who I assumed knew more than it turned out they did. “Noble savage!” and “Rousseau!” would be disdainfully disgorged, intended as insults which were supposed to end all debate, “Give the Indians chainsaws and they’ll cut the forest down as fast as anyone!” That was two generations ago, and time has proved how wrong they were. Satellite imagery of the Amazon now reveals, beyond any doubt, that the forest remains largely intact where Indigenous people retain control. In fact, the most biodiverse areas on Earth are Indigenous territories, and it’s reckoned that today they incorporate an astonishing eighty per cent of all floral and faunal diversity on the planet. Some Amazon Indians do have chainsaws and could have felled everything, as those anthropologists used to howl (and big conservation organizations still do – at the same time as they partner with logging companies!), and some Indian peoples do sell their timber. But they certainly didn’t destroy the forest, as predicted: In fact, if you now take an aerial picture of Amazonia and draw a line around the areas of visibly intact forest, you’ll likely be tracing the exact outlines of Indigenous peoples’ territories. That is confirmed by the data newly available through satellite and GPS technology: Deforestation on land managed by agribusiness, around the Pimental Barbosa Indigenous Reserve in Brazil for example, leapt from 1.5 per cent in 2000 to twenty six per cent ten years later. In the same period, deforestation inside the reserve, managed by the Xavante Indians, was reduced from 1.9 to 0.6 per cent. Similar figures can be seen throughout the region, where deforestation outside Indigenous areas is up to twenty times higher than inside. Areas managed by Indigenous people in the Amazon have even lower deforestation rates than protected areas such as national parks. We find the same story elsewhere. Tribal peoples in India hold particular forest areas especially sacred; they are now recognized by scientists as “biodiversity hotspots.” The Loita hills and forests in Kenya remain largely intact because the local Maasai council of elders banned tree felling without its explicit permission. The Karura forest, well inside the city of Nairobi, also owes its preservation originally to the traditional owners, and a belief in the curses they placed on anyone who might allow in settlers. Data comparing dozens of state- with Indigenous-owned forests over three continents found unequivocally that communities really do protect their lands and preserve forests, even if that means taking less for their own livelihoods. Of course, it’s also important they have confidence in the future security of their land rights. Impressive and moving stories are growing about how Indigenous communities are making their own new rules for conserving their lands and then policing them, imposing fines, arresting loggers, and even stopping government departments from imposing their irresponsibly harmful policies. This is happening from Brazil, where it is exemplified by the “Guajajara Guardians” protecting the lands of Awá Indians, to India. In the latter country, home to more tribal people than any other nation, government policy calls for more teak and eucalyptus plantations, and cynically trumpets this as increasing “green cover.” But these trees don’t provide forage for elephants, which are forced to look for food in villagers’ fields, and inevitably turn dangerous. Community run projects are retaliating by establishing forest corridors both to reinforce tribal self-sufficiency and to provide elephant habitat. Time and again, governments and their advisors prove inept at conservation when local people have long known what actually works, but are often forbidden from doing it. It’s not just in forests and savannahs where Indigenous peoples can lay convincing claim to being the best conservationists. The Lax Kw’alaams people on Canada’s Pacific coast turned down the equivalent of over a quarter of a million U.S. dollars for every man, woman and child when they refused to allow a gas terminal on their land. As artist Lianna Spence said, “We already have a lot of benefits around us – we have… salmon. We have halibut, crab and eulachon. Those are our benefits.”

Around the world – though only where they are politically strong and numerous enough – Indigenous peoples are now blocking proposed “development” sites and tourist roads, rejecting financial compensation, filing legal complaints, and fighting to stop the environments they depend on – which, remember, they have created themselves – from being torn from their stewardship. Their role in the vanguard of true conservation is slowly beginning to be acknowledged. Unfortunately, this is almost always with little more than hot air – grand declarations not reflected in action. Worse, it remains the norm for conservation projects to encourage the eviction of Indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands, which usually destroys them. The major conservation organizations remain guilty of this illegal and counterproductive measure, notwithstanding their public relations departments’ pretense that they changed years ago. Vithal Rajan, an Indian former head of the World Wildlife Fund’s “ethics department” told me that he left the job (which paid more in a year than he had previously earned in ten) because WWF promised him they would start treating tribal peoples as environmental guardians, “but then went on with their élite strategies.” He described his role as a, “brown man who could talk English, wear a dinner jacket, stand with Prince Philip, and be nice while the audience of multimillionaires wrote cheques.” The truth is that Indigenous peoples were practicing sensible and balanced resource management long before the invasion and takeover of their territories, and long before the colonial conservation organizations appeared, convinced that only they knew best. In summary, tribal peoples managed their environment: by undergrowth burning; by changing and moving plants and animals; by opening clearings; and by controlled hunting and fishing. The result was an environment heavily modified to create a better space for people to live their lives, and one that brought a vastly enhanced biodiversity. The opposing idea, still believed by many, that the most intelligent animal on our planet for several million years had only a nominal impact on the environment, is actually very strange if you think about it. It turns out to be just a romantic, and recent, Western belief. It gained traction in the nineteenth century, influenced by Romanticism, scientific racism, and (as I have argued elsewhere) that aspect of Reformation theology that emphasizes a separation between corrupt humankind and God’s supposedly untrammeled Nature. The Industrial Revolution, beginning in Europe and spread through conquest, of course changed the planet in new and alarming ways. Amassing more and more things and power were its tenets; the provincial dogma that everything must become uniform and simplified, that there was only one correct way of looking at the world, was trumpeted with a ferocity that has endured, and it remains the prevailing faith today. In spite of waves of doubt, including both the hippy and green movements, it’s the belief that now governs many Westerners, especially those with power and privilege. It also motivates non-Westerners who are, perfectly understandably, taught to aspire to the same way of life, though only a tiny number will ever be allowed to approach, let alone attain, it. Where does this leave the “noble savage” jeer, flung at those who support tribal peoples? The truth is that we can now unequivocally declare Rousseau’s allegory to be both right and wrong! Tribal peoples don’t just live “in nature,” or, if they do, it’s a nature that they themselves have created. On the other hand, they do live in a way that is broadly and sensibly balanced with an environment that they depend on for their livelihoods, and they really do make the best conservationists. They are not all perfect, but they certainly do a far better job of it than the bloated, big, colonial conservation organizations, which are usually deeply embedded in a wider government-industrial complex serving primarily itself and rich tourists. Some conservationists blame humans for some prehistoric megafauna extinction, in spite of the overwhelming evidence that people lived alongside big animals for thousands of years, and still do in some places. (A recent theory from Madagascar is that – paradoxically – it was not hunting societies but farmers who brought about the end of the megafauna there.) Other conservationists defend their elitism by admitting that tribal peoples might have once been good conservationists, but claim the original balance between tribes and nature has been irredeemably upset since Indigenous people have become “tainted,” seduced by consumerism and are now “just as bad as the rest of us.” In some places this may ring true. However, if we stick to known facts, and most importantly if we really do value biodiversity, then the evidence is clear that we have to stop alienating contemporary tribal peoples by throwing them off their land. It harms wildlife protection because it turns them into enemies of conservation and means we can never learn from their environmental knowledge and expertise. For their sake, for that of the environment, and indeed for all humanity, we have to start valuing them as the best experts. We need to start realizing that we’re no more than junior partners in this vital quest to save “nature” from ourselves.

There’s nothing “romantic” about this, it’s common sense supported by myriad, growing, and provable facts. If we accept it, it could lead industrialized society towards new and better relationships between the vast diversity of peoples, animals and plants of our planet – and their very deep interconnectedness about which our knowledge remains scanty and shallow. It would be a game changer for all our futures. That obviously means shifting our attitudes and revising the know-it-all mentality that the West has become addicted to over recent generations. However, it does not imply a complete abandonment of industrialization, or any requirement that “we” live like we once did. A few may think these desirable goals, but they simply won’t come about to any significant extent – which is fortunate because if they did they would harm millions. So, incidentally, would the dream of those like E.O. Wilson who wants to put half the world off limits to everyone but conservationists – thankfully, there’s little chance of that nightmare ever happening either (though they’re having a good go at imposing it on Africa). Perhaps it would also be helpful if conservationists stopped complaining about “overpopulation” – all too often meaning there are too many black and brown people. Women’s empowerment and access to contraception are vital and must be supported, but the fact is that the population density in Africa remains low. South of the Sahara it’s just ten per cent that of England, and less than half that of the United States. It takes about forty Africans to consume the same as a single American. Environmentalists wanting to reduce the population to ease the pressure on resources might find it most efficient to focus first on wealthy Americans and Europeans (and remain childless themselves of course!). Nostalgia might be hard to shake off, but it’s not a useful recipe for living tomorrow. At the same time, the current drive to consume more and more should be recognized for what it is, an unhinged gateway which leads inexorably towards a real wilderness, one so barren and hostile that only the most powerful are likely to have much chance living in it. That may suit some of them just fine, but whether or not they are allowed to get away with it may well end up being a question of how much fight there is in the rest of us.

Stephen Corry has worked with Survival International, the global movement for tribal peoples, since 1972. The not-for-profit was instrumental in stopping the Botswana government evicting the Bushmen from the Central Kalahari Game Reserve in Botswana. It works in partnership with tribal people to help them prevent their land being stolen, including for conservation. Survival has an office in the San Francisco Bay area. Its public campaign to change conservation can be joined here. This is one of a series of articles on the problem.