Bringing a katsina home

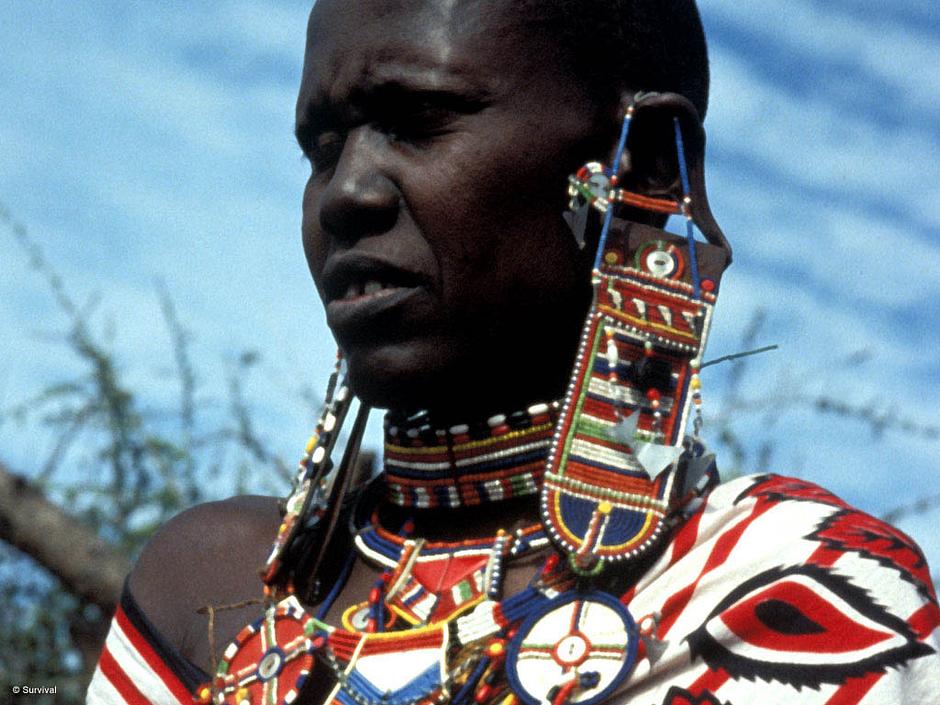

The katsinam (‘friends’) of the Hopi tribe of Arizona are the spirits of ancestors, important animals and the natural world. Katsinam appear during the sacred dances that maintain the balance between the Hopi people and the spirits. The dancers sing for rain and for the melting snow to irrigate their crops; they mark the first sight of the new moon and honor the relationship between man and eagle.

In April 2013, as the Paris auction house Néret-Minet Tessier & Sarrou was preparing to auction 70 katsinam, the Hopi tribe wrote to the auctioneers asking them to cancel the sale on the grounds that their public display and sale caused them grave offence. ‘The mere fact that a price tag has been placed upon such culturally significant and religious items is beyond offensive,’ said Leigh Kuwanwisiwma, director of the Hopi Tribe’s Cultural Preservation Office. ‘They do not have a market value. Period.’

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, or NAGPRA, is a U.S. law enacted in 1990 to protect the ancestral remains and sacred objects of American Indian tribes. Unfortunately, a similar law does not exist in France.

Acting pro bono for Survival International and the Hopi tribe, Pierre Servan-Schreiber, a partner in the law firm Skadden Arps, obtained permission from a Paris judge to summon the auction house to a court hearing, but sadly the bid to cancel the sale was eventually thrown out, and the auction went ahead. Pierre then purchased one of the katsinam himself at the auction so it could be returned to the Hopi and, together with three Survival representatives, brought it home to the Hopi.

In an exclusive interview for Survival International, Pierre Servan-Schreiber talks about how he fought the case as if he were a Hopi himself, his journey across Arizona by motorbike and how the Hopi ‘lost the battle, but not the war’.

Leila Batmanghelidj and Kayla Wieche of Survival’s San Francisco office also witnessed the restitution ceremony, together with Jean-Patrick Razon of Survival France. Leila recounts here the warm welcome they received from the Hopi, how the katsinam are integral to the Hopi way of life, and conversations shared with the Hopi about the similar struggles of tribal peoples worldwide.

Interview with Pierre Servan-Schreiber

Pierre Servan-Schreiber, how did you become involved in the Hopi katsinam case, and why did you take it up?

Skadden is a member of an association called the Alliance of Lawyers for Human Rights, which is a forum to which NGOs in need of pro bono legal advice can send their questions. The association then sends questions to member firms. Whichever firm raises its hand first, so to speak, is allocated the work.

What inspired Skadden to ‘raise its hand’?

I thought the question from Survival was an interesting and intellectually challenging one: can an auction be suspended on the grounds that the items to be sold are i) considered as sacred and non-saleable by those who made them and ii) were, potentially, and even probably, stolen from the people to whom they belong.

One of my associates told me that he would like to take up the case, so I suggested that we work on it together. One of the attractive features of the assignment was that it made for a drastic change to the cases on which I usually work.

We received the email from the Alliance on the morning of Monday, April 8, 2013. The auction sale was taking place that Friday, April 12 at 2 pm. We had to get in touch with Survival International, prepare an engagement letter, check as to whether there was any conflict of interest, and so on. We also needed to make sure that the Hopi tribe was on board, as I believed it would make our case stronger. Time was limited.

Were you confident that you could win the Hopi case?

I knew the odds were not in our favor. But even if we lost, I believed it to be one those rare legal cases whose media coverage would help change public opinion. So, to my mind, it was well worth fighting for anyway, and as we were working on the case on a pro bono basis, the Hopi people and Survival had nothing to lose in trying.

The evening after the Court’s judgement, I spoke with the Hopi tribal council by phone. I told the Hopi that we had lost the battle, but not the war; that eventually a Court would rule that not everything in this world could be bought or sold.

Why did you think it is important that the katsinam should be returned to the Hopi?

I quickly understood the vital significance of the katsinam for the Hopi. The fate of the katsinam and the Hopi people is completely intertwined.

I felt that selling 70 katsinam – the most important collection in the world – was, for the Hopi, comparable to selling a piece of the cross on which Jesus Christ was crucified, or selling the relic of a Saint for Catholics: that is, something so deeply rooted in their religion that putting it up for sale to the best bidder was simply inconceivable.

The outcome was unfortunate, as the katsinam will now be sold and dispersed, and the likelihood that they will eventually return to their true home with the Hopi is severely reduced.

But I fought the battle as if I was a Hopi myself.

What argument did you use to promote the Hopi’s case?

The law in the U.S. that protects Indigenous artifacts carries no weight overseas, thus in France there was no legal provision for the katsinam. So we had to adopt French legal precedents to carry our argument. These were:

1) A Supreme Court ruling exists in France whereby graves and funeral items cannot be bought or sold. So my argument was based on the sacred function of the katsinam today, their relationship to those who have passed on, and their role as the embodiment of the spirits of the dead. The Hopi relationship to katsinam is similar to our relationship in France to sepulchres, and to the way in which we pray to the deceased at their gravesides.

2) Another body of French Supreme Law provides that where an object has been in a given family (in this specific case, the d’Orléans family, the former French Royal Family) for generations, one family member is not allowed to sell the object, as it belongs to the family as a whole and not to one single member, hence making it improper for sale.

Therefore our argument was, that although there was no specific statute in French providing for restrictions to the sale of katsinam, such case law gave enough legal grounds to suspend the auction sale.

The Paris judge ruled that, ‘in spite of their sacredness to the Hopi, these masks are not bodies or body parts’. What is your view on this?

I really disliked this part of the judgement. We didn’t argue that katsinam were bodies or body parts. We simply said that they were considered by the Hopi to be living things. To me, this is the way in which the judge justified the negative outcome of the case. The fact that she did not respond to our arguments, which were based on French case law, and went on to find an article in the Civil Code that had nothing to do with the case, suggested to me that she was uncomfortable answering our questions directly.

Why did you buy a katsina? Do you know anything about what this specific katsina represents?

I didn’t plan to buy one! After the Court’s judgement, I took my associate and Jean-Patrick Razon from Survival France’s office out to lunch, where they told me that they would be going to the auction.

It struck me then like a lightning bolt: I had to try to get a katsina and return it to the Hopi. I saw it as a symbolic gesture that all had not been lost and that the battle had not been in vain. So I gave my colleague a budget, and asked him to buy a katsina for me. My colleague sent me a message later, telling me that I was the proud owner of item no. 13.

What laws do you think should be in place for similar sales in the future?

I believe that for an item to be prevented from being sold, certain criteria need to be applied:

1) The item itself should be considered sacred by the people who created it. For example, a figurine of the Virgin Mary would not meet this criterion, as it is the Virgin Mary herself who is sacred to the Catholics, not a figurine. Similarly, katsina dolls – who represent the katsinam themselves – are not considered as sacred by the Hopi and can be freely bought and sold.

2) The religion or culture must be still alive today (which, for example, eliminates artifacts made by the Aztecs).

3) The items must not be found for sale anywhere in the world. Therefore, copies of the Holy Bible, Qurans and other sacred text would not be covered by this criterion, as they can be freely bought and sold.

Can you describe your trip to the Hopi tribe in Arizona?

The whole experience of the Hopi court case was a journey. Until I went to Arizona, it was a journey that I experienced from my desk, but a fascinating one nonetheless.

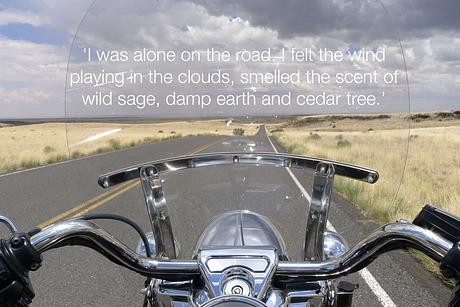

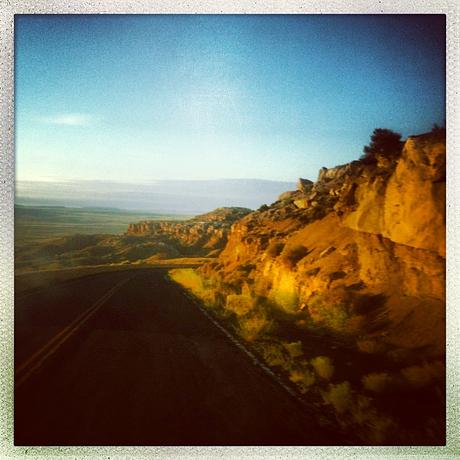

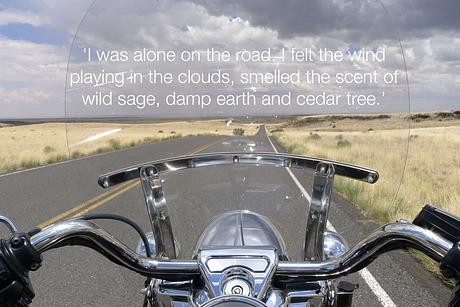

I felt that the returning of a katsina to the Hopi was a symbolic act that needed to be accompanied by further symbolism: the physical journey to Hopiland. For me, the only way to make such a journey was by motorcycle. I told the Hopi in a speech I made that I had been riding motorcycles nonstop since I was 14; that biking had helped me to define who I was during the difficult stage of adolescence, which is why I had made the journey to Hopiland by bike.

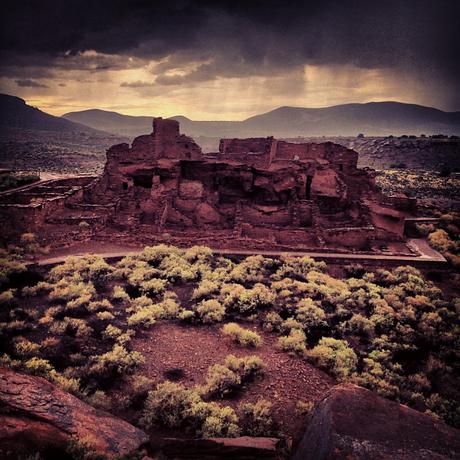

For that hour en route to the Hopi, I felt the wind playing in the clouds, smelled the scent of wild sage, damp earth and cedar tree; I saw the sun’s rays streaming through storm clouds and painting the rocks a vibrant red hue.

I was alone on the road, and I don’t mind telling you that I felt choked with emotion by the beauty around me.

Can you tell us about your days in Hopiland?

I spent four days with the Hopi in their land, Hopituskwa. I met political representatives of the Hopi tribal council together with religious leaders. They were extremely welcoming and emotional. I was greeted as if I had brought back the corpse of a son who had died in combat. It was that powerful.

To illustrate this level of emotion, I had kept the katsina with me throughout the 15-hour flight from Paris, and was carrying it when I arrived at Flagstaff airport. A Hopi woman was at the airport to greet me. She burst into tears when they saw me, even before she had said ‘Hello’.

Can you describe the restitution ceremony?

The restitution ceremony took place in private, in a window-less room. There was nothing fancy or festive about it. Similarly, and to continue the analogy, the homecoming of a son’s body from battle would not be a joyous occasion.

The two things I will never forget are the moving words that two members of the Hopi whispered in my ear, and the fact that I was invited to bless the katsina before the priest took it away.

The Hopi gave me a katsina doll, a small sculpture that represented a frog katsina. As a Frenchman, I thought this was highly appropriate!

Can you tell us a little about the Hopi’s ‘Home Dance’?

I was invited to attend one of the Hopi dances, the Home Dance, which is the last dance of the year. Most of their dances are about the important relationship the Hopi people have with rain and corn, life and death, giving and receiving and their connection with the environment.

Very few non-Indigenous people have seen the dances. It is not that they are secret, but that non-Hopi people do not know when and where they will take place, and for those that find out, few are willing to spend an entire day, from sunrise to sunset, standing under a scorching sun watching the dances.

It would be too difficult for me to describe the dances in a way that would express their uniqueness. Let me just say that when one sees sixty katsinam emerging from a kiva (a ceremonial building) in the pure light of the rising sun, who then walk in line to the sound of the rattles they wear towards the centre of the village where the entire tribe waits in silence for them, one knows that something entirely unforgettable has been witnessed.

No cameras, videos or smart phones are allowed in the Hopi villages. No one is allowed to draw or sketch, so there are no visual representations of the dances.

Can you tell us what you have learned about Hopi beliefs?

I was struck by the communal nature of their philosophy. Through katsinam, they pray for the rains to come, but it is also a way of praying for peace in the world – not just peace between men, but between man and nature.

The Hopi believe that humans have passed through four worlds, and that each world has been destroyed because humans were not good enough to deserve life. Only a few morally strong men were allowed to move to the next world.

Hopi prophecy states that in the next world, the Hopi will have a choice as to whether to live in harmony with natural elements such as the wind or rain, or whether to choose a different path. Choosing a different path could signify the end of the Hopi as a people.

When I look at the world today, it is easy to think that we are not heading in the right direction, and that the Hopi prophecy might ultimately be true.

A few days with the Hopi

In July 2013, my colleague Kayla Wieche and I had the honor of being invited, together with Pierre and Survival France’s Director, Jean-Patrick Razon, to the Hopi reservation, to take part in the restitution of the katsina and to witness the annual Home Dance ceremony.

With a population of approximately 18,000 people, the Hopi people of northeastern Arizona live across 3 mesas among 12 different villages. After a journey through the Mojave Desert, we welcomed the lush, green flora of Flagstaff, Arizona. Flagstaff has a unique climate with rare plant life – the San Francisco peaks host plant species that do not exist anywhere else in the world.

On the morning of the restitution we met with the Chairman of the Hopi tribe, LeRoy Shingoitewa and other tribal council members, administrative staff and religious leaders.

We spent the morning listening to stories from the tribal council and religious leaders; how they achieved positions of leadership and how religious leaders are given responsibility as children to fulfill duties until they are no longer physically able – a lifelong honor, and a lifelong responsibility.

In a private, emotional moment, Hopi religious leaders fed the katsina with cornmeal, a ritual intended to nourish the katsina after being away from its ancestral land for so long. An object sacred to the Hopi had finally been returned.

The Niman, or ‘Home Dance’ is the last in the Hopi’s annual cycle of ceremonies and signifies the katsinam’s return to their spiritual home in the San Francisco Peaks. We woke early to witness the important dances that take place from sunrise to sundown. We were welcomed with boundless warmth and appreciation when visiting several homes and shared conversations with Hopi men, women and children about the importance of the katsinam and how their role is integral to the Hopi way of life. We talked about Survival’s worldwide campaigns, and the parallels between the Hopi’s struggles and those of other tribes.

It is our hope that, thanks to the global media coverage of the auction, other auction houses, art dealers and individuals will think twice before placing monetary value on sacred objects that are the rightful property of the Hopi.

Photos of the trip by Jean-Patrick Razon, Director of Survival (France).