Death in the Devil’s Paradise

Little over a hundred years ago, in March 1913, one of the least known, and most shameful, episodes in British colonial history was brought to an end in a London court room. The Peruvian Amazon Rubber Company was wound up in the High Court, the only hint at its dark secrets being a brief remark by the judge that ‘it was impossible to acquit the partners of knowledge of the way in which the rubber had been collected for the company’.

What is known today as the rubber boom had its origin in the middle of the nineteenth century, with Charles Goodyear’s discovery that cooking and treating latex harvested from rubber trees turned it into a product with a huge range of potential uses. With Henry Ford’s mass production of the motor car a few decades later, and the invention of tyres by John Dunlop in 1888, the need for rubber suddenly became extremely pressing.

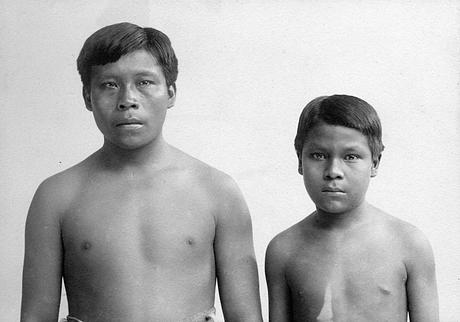

The rubber tree grew in profusion in the Amazon, especially in its western fringes, and soon a veritable ‘rubber rush’ was on. Entrepreneurs and fortune-seekers set off into the steamy jungle determined to cash in. Unaware of the impending disaster, tens of thousands of Indians for whom the western Amazon was home were experiencing their last years of peace.

One of the many chancers and treasure-seekers determined to make their fortunes in this brave new world was a Peruvian trader named Julio Cesar Arana. Arana acquired vast estates in a region named after its largest river, the Putumayo, and, as many others were doing at the time, realized that only by enslaving huge numbers of the local Indians to collect the latex could his visions of vast wealth become reality. (Slavery had, of course, been abolished decades earlier in the US, but brazenly continued in Amazonia).

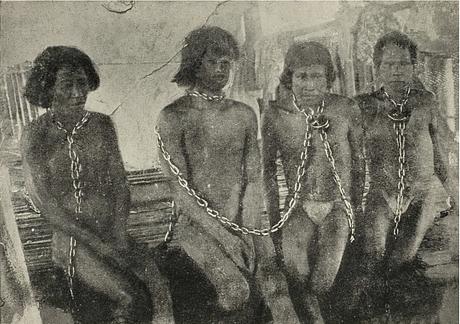

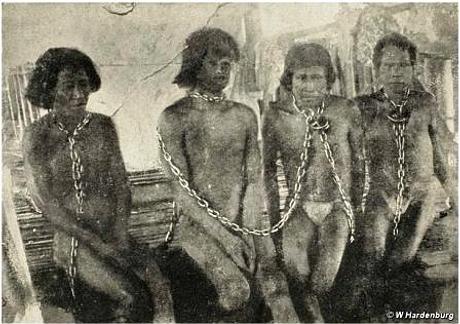

Arana and his brother, the aptly-named Lizardo, moved quickly, bringing to Peru from Barbados a large number of overseers well-used to cracking the whip on workers in the British sugar-cane estates. The Bora, Witoto, Andoke and other tribes living in the Putumayo basin were quickly enslaved, and those who escaped the appalling treatment inflicted on them soon fell victim to waves of epidemics brought into remote rivers by traders and rubber-tappers.

In a few short years, thousands of Indians were killed or died from mistreatment or disease. The outside world remained unaware of the horrors the Arana brothers’ empire was perpetrating until 1909, when a young American engineer, Walter Hardenburg, who had traveled through the region the year before and been held prisoner by the Arana brothers, wrote several articles for the magazine Truth.

Hardenburg’s account of the abuses he had witnessed makes horrifying reading even today. ‘The agents of the Company force the pacific Indians of the Putumayo to work day and night… without the slightest remuneration except the food needed to keep them alive. They are robbed of their crops, their women and their children… They are flogged inhumanly until their bones are laid bare… They are left to die, eaten by maggots, when they serve as food for the dogs… Their children are grasped by the feet and their heads are dashed against trees and walls until their brains fly out… Men, women and children are shot to provide amusement… they are burned with kerosene so that the employees may enjoy their desperate agony.’

This came as a huge embarrassment to the British establishment for, two years previously, the Arana brothers had come to London to raise capital for their burgeoning empire. Their tales of immense fortunes to be made in this remote corner of the world of which most Londoners knew nothing had found a willing audience. After listing on the London Stock Exchange and recruiting a British board of directors, the Arana brothers had headed back to the Putumayo with £1million of fresh finance in their pockets.

The outcry over Hardenburg’s testimony prompted anxious debate in Parliament, and a growing disquiet which the government eventually found impossible to ignore.

In 1910 a commission was sent to the Putumayo to investigate. One of its members was the British consul in Rio, the Irishman Roger Casement. Casement’s subsequent report, after traveling extensively throughout the Putumayo, upheld Hardenburg’s account, with a good deal more shocking detail. Hardenburg himself later published an account of his travels, entitled ‘Putumayo: the devil’s paradise’.

The Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, set up a parliamentary select committee to decide what should be done. The committee’s report indicted the directors of the Company: directors ‘who merely attend board meetings and sign cheques… cannot escape their share of the collective moral responsibility when gross abuses under their company are revealed.’ Julio Cesar Arana ‘had knowledge of and was responsible for the atrocities perpetrated by his agents and employees in the Putumayo.’

The writing was on the wall not just for the Company, but for the rubber boom itself. Rubber tree seedlings brought from the Amazon to London and subsequently to Sri Lanka and Malaysia were finally being successfully propagated. Within a very few years, vast plantations were being established in Asia, and the Amazonian empire built by Arana and dozens like him had crumbled to dust.

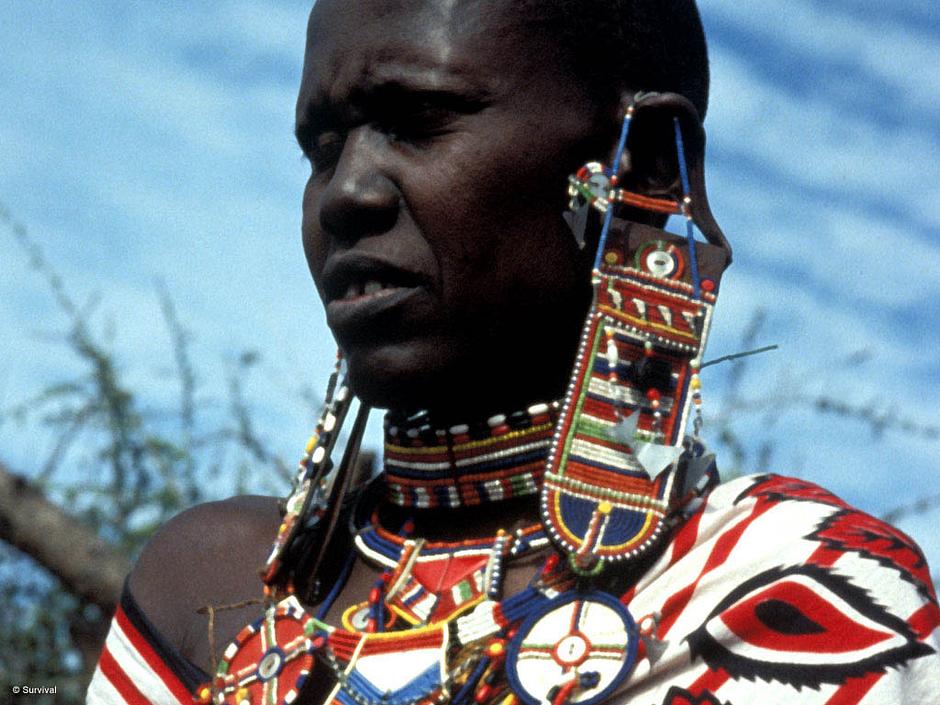

For the Indigenous peoples who were the boom’s principal victims, the consequences have been far-reaching. Many tribes were completely wiped out. Others, like the Witoto and Andoke, survive today, but the atrocities they endured just a few generations ago still remain vivid in their memory.

Fany Kuiru, a Witoto woman, said recently to a Survival researcher, ‘As long as humanity fails to recognize its faults and errors, or fails to respect the differences between people, and as long as greed remains the rule for dominating other people, we are condemned to repeat history.’

And history is indeed repeating itself, as the industrial world’s insatiable hunger for natural resources persists unabated. Just a short distance from where Arana established his headquarters in the Putumayo, Peru’s Matses tribe have vowed to resist attempts by a Canadian company to enter their territory. This time, oil is the lure. And nearby, other tribes – the Nanti, Nahua and Matsigenka – see gas pipelines and drilling wells mushrooming as they find themselves in the middle of the Amazon’s biggest gas project, on the Camisea River.

The ghosts of Hardenburg and Casement would find it a terrible irony that a century on from the holocaust they bore witness to, Amazon Indians continue to fall victim to our rapacious greed, a greed that consumes all in its path no matter the human cost. Surely they deserve a little peace?