'For all peoples of the world are men.'

© Public Domain/Survival

© Public Domain/SurvivalBartolomé de las Casas, protector of Indians, was a 16th century Spanish missionary with a passion for social justice.

After they had tied him to the stake but before they lit the fire, Hatuey, an Indian leader, was offered a spiritual reprieve by a Spanish priest. Would he like to ensure the certain passage of his soul to heaven by embracing Christianity? he was asked.

Hatuey contemplated the proposal. ‘Are there people like you in heaven?’ he replied. When the priest reassured him that there were, Hatuey responded that he would prefer to go to hell, where he would not know such cruel men.

Hatuey died 500 years ago, on the island of Cuba. The people he wanted, at all costs, to avoid – even at the risk of eternal damnation – were the Spanish conquistadors.

The Indian leader’s death was instrumental in shaping the seminal beliefs of one man: Bartolomé de las Casas. He was a slave owner-turned-Bishop-turned-chronicler who raged a life-long battle against the murderous injustices meted out to South American Indians by the colonists.

‘The spectrum of missionary work around the world covers three quite different attitudes, and much in between,’ says Stephen Corry, Director of Survival International. ‘There are those, like Bartolomé who view their mission as one of standing with the downtrodden against the oppressors; others see their job as extending the imperial power of their church; still others are focussed on saving human souls at whatever human cost.’

As ‘protector of Indians’, de las Casas was one of the first missionaries to uphold the rights of the oppressed and protect the lives of Indigenous peoples.

© Public Domain/Survival

© Public Domain/Survival

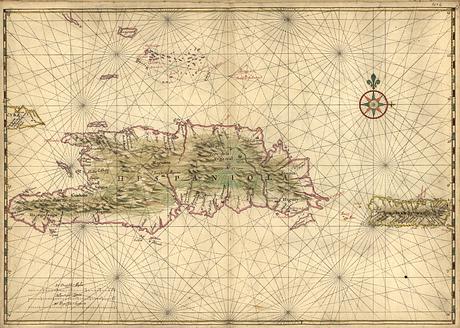

A contemporary of Christopher Columbus, de las Casas had travelled in 1502 to La Española, a Caribbean island now known as Haiti and the Dominican Republic, which at the time was inhabited by the Indigenous Taínos people. On landing, the Spanish settlers already on shore reportedly told the new arrivals, ‘The island is doing well, because much gold is being mined.’

Initially he settled as a merchant and encomendero – an Indian slave owner – on ‘a hill almost encircled by a beautiful and sparkling little river’, and recounted that ‘these people are the most guileless, the most devoid of wickedness.’

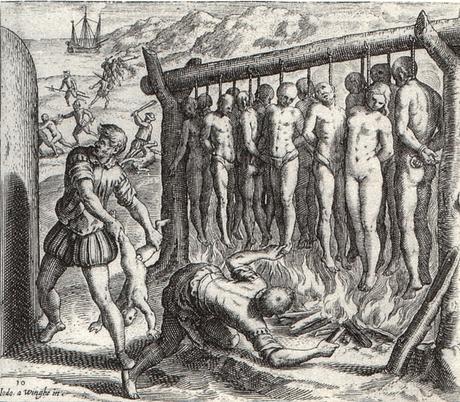

If the Indians were devoid of wickedness, the conquistadors made up for it. It is thought that when the conquistadors arrived in the Americas, there were 100 million inhabitants. 90% died on contact, many succumbing to diseases, to which they had no immunity, brought in by the Europeans.

Those who didn’t die from imported diseases were treated with ‘strange cruelty’ by the aggressive invaders. They fed Indian babies to dogs, hunted adults for sport and roasted men alive. ‘They think no more of killing ten or twenty Indians for a pastime, or to test the sharpness of their swords,’ wrote de las Casas, continuing:

’One day … the Spanish dismembered, beheaded or raped 3,000 Indian people. They cut off the legs of the children that ran before them. They poured people full of boiling soup. I saw all the above things … and numberless others.’

De las Casas also saw, with rare insight, the ulterior motive of many conquistadors. Though the Spanish carried the Requerimiento – a royal document that outlined Spain’s divinely ordained right to sovereignty – into every battle, de las Casas believed that spreading the word of God was largely a ruse: an expedient mask. Ambition, not altruism, was the driving force; gold, not God, was their goal.

He believed that the conquistadors slashed and slaughtered their way like ‘ravening wild beasts’ across the ‘New World’ not solely in homage to Christ, but to ‘swell themselves with riches’. He suspected they had crossed the Atlantic not only to spread the word of the Lord, but to find the gold that washed through the rivers of Amazonia and the minerals that lay beneath their rampaging feet. ‘Our work,’ de las Casas said, ‘was to exasperate, ravage, kill, mangle and destroy.’ The conquistadors destroyed lives and lands, and they told the Indians that to save their souls, they would need to become Christians.

© Public Domain/Survival

© Public Domain/Survival

The systematic eradication of Indigenous ways of life and beliefs is still used as one of the most potent weapons in the oppression of tribal peoples. Such is the religious zeal of some extreme evangelist groups today, that they still promulgate the line that people are condemned to hell unless they adopt Christianity.

In extreme examples, contemporary missionary organisations such as the New Tribes Mission have even set out to force the first contact with tribal peoples, with devastating and destructive consequences.

‘Whether or not tribal peoples die in the process from alien illnesses seems to be relatively unimportant to some missionary groups when compared to securing heavenly eternity,’ says Stephen Corry.

If the greed of the conquistadors knew no bounds, neither did the integrity and outraged courage of de las Casas. Revolted by the hypocrisy of men who proclaimed pious inspiration while distributing the horrors of hell, he was also influenced by a group of Dominican preachers who asked the conquistadors, ‘Tell me, by what right do you hold these Indians in such a cruel and horrible servitude? Are they not men?’

De las Casas reformed his views, giving up his Indian slaves around 1515, and set about exposing the lies. He felt morally bound to inform the Spanish court what was being carried out in the name of Christ.

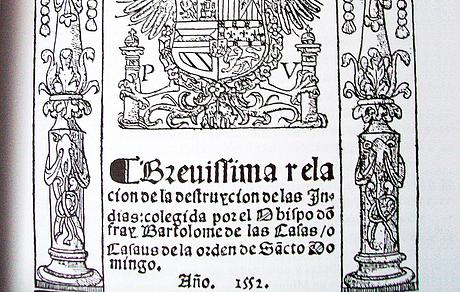

‘So as not to keep criminal silence concerning the ruin of numberless souls and bodies that these persons cause,’ he wrote, ‘I have decided to print some of the innumerable instances I have collected in the past and can relate with truth.’

These truths, which became extensive writings about the mistreatment of the Indians – one of the most famous being A Short Account of The Destruction of the Indies – were instrumental in prompting King Charles V to issue his ‘New Laws’ in 1542, which abolished slavery and the encomienda system, and resulted in the liberation of thousands of slaves.

© Public Domain/Survival

© Public Domain/Survival

Today, de las Casas is thought of as an early human rights’ activist and considered by some as a father of liberation theology, a concept fostered as a movement in the early 1960s which believes that the Church should act to bring about social change.

‘The liberation missionaries from the 1960s on saw their Christian work as de las Casas saw his,’’ says Stephen Corry. ‘They did not believe that they were working to convert the heathens, but to help those in need. De las Casas was very much in the vanguard of this missionary approach.’

Such beliefs are often held, however, at great personal cost. De las Casas suffered the disapproval, anger and threats to his life of many of his contemporaries; many missionaries since him have been murdered for their humane principles.

De las Casas was driven not by a self-regarding agenda but by a deeply-rooted sense of justice. ‘There are many others like them, who stand shoulder to shoulder with tribal peoples. But sometimes they pay the highest price for their compassion,’ says Stephen Corry.

The man who sang the first mass held in the Americas was also one of the first to defend the lives and lands of the continent’s Indigenous peoples. De las Casas knew the Indians were not inferior to their oppressors. He knew that ‘all the peoples of the world are men’ – rational human beings, part of a single common humanity. ‘For all people of these our Indies are human … and to none are they inferior,’ he said.

‘I shall do my endeavour, if God grant me life,’ he wrote. He was granted 92 years of life. Until his death in 1566 in a Madrid convent, he worked to end the racist oppression of South American Indians, and continued to decry the hypocrisy and cruelty of the conquistadors.

© Public Domain/Survival

© Public Domain/Survival