Indigenous languages hold the key to understanding who we really are

For every language that goes extinct, we lose a vital piece of the human puzzle.

Languages are one of the greatest emblems of human diversity, revealing just how astonishingly differently it’s possible for human beings to perceive, relate to, and make sense of the world. They are also the finest libraries in existence, in which we find the collective history, knowledge, mythology, and perceptions of an entire people. But this diversity is being lost at an alarming rate. Some experts would go as far as saying that 90% of the world’s languages are at risk of disappearing. But why does the loss of Indigenous languages matter? Read on to find out why Indigenous languages are fundamental to understanding the world we live in, who we really are and what humans are capable of…

‘Children © Forest Woodward / Survival, 2015

Languages die because people stop speaking them: due to social pressures, demographic change and external forces. Colonisation, and the globalised capitalism it subsequently spawned, has perhaps been the greatest murderer of languages in human history, and this legacy is alive and well in the present. Survival International is campaigning against Factory Schools, which actively contribute to language death by teaching tribal children not in their mother tongue, but only in the dominant dialect or the official language of the state. This systematic cultural erasure threatens the lives of millions of children, their families, Indigenous communities, and the survival of languages around the globe. Our campaign against Factory Schooling will launch later this year; sign up to our mailing list for updates.

There are around 7000 languages spoken on Earth, but 23 languages are spoken by around half of the world’s population. On the other hand, nearly 3000 languages are considered endangered, meaning that almost half of the planet’s current linguistic diversity is under threat.

The most linguistically diverse place on Earth is the island of New Guinea, which is split into the independent state of Papua New Guinea, and West Papua, which is under Indonesian occupation. In an area of 786,000 km², approximately 1000 languages are spoken. Compare this to Europe, where around 100 languages are spoken in an area of over ten million km².

There is a strong correlation between linguistic diversity and biodiversity; where there are most species of plants and animal, there are most languages spoken. Languages are closely connected to the environment they are spoken in, so in such areas they contain rich, detailed and technical knowledge about the flora, fauna, and habitat of that area. When a new species is “discovered” by scientists, you can bet your bottom dollar that the tribal people living in that area would already have had a name for that species and be highly knowledgeable about it. These languages are ecological encyclopedias, and, as they are for the most part unwritten, if they are no longer spoken, then this wisdom and understanding is lost to humanity forever. Biological diversity and linguistic diversity go hand in hand; if one is threatened, then so is the other.

Soliga are the eyes and the ears of the forest. They recognize the smell of different animals and can deduce the personality of an elephant by just looking at the way it holds its trunk! BRT Tiger Reserve. © survival

Around half of all the world’s languages have no written form, but this certainly does not mean they are lacking in culture. Unwritten languages are rich in oral traditions; stories, songs, poetry, and ritual passed down through the generations that remain remarkably consistent and reliable through time. Scientists are finding more and more evidence for events that happened thousands of years ago which have been documented and preserved in Indigenous storytelling, re-told and impressively preserved over hundreds of generations.

No human being on Earth speaks a “primitive” language; there is simply no such thing. All languages have intricate and unique rules of sound, words and grammar that all the speakers of that language know and understand intuitively. In fact, Indigenous languages generally tend to be the most complex, specialised and idiosyncratic, especially those spoken in remote areas by only a few hundred people. Big global languages like English, Spanish or Mandarin Chinese are relatively simpler and on the whole follow more predictable patterns. Because of this uniqueness, the languages which are most at risk are arguably those that have the most to teach us about the incredible breadth and variety of human perception and experience.

Some Indigenous languages demonstrate that human speech is not limited to the spoken word. Most famous are perhaps the African drum languages, allowing messages to move between communities at 100 miles an hour. There are also around 70 languages that can be whistled. This isn’t like whistling the tune of a song, it means actually whistling in words and sentences with the flexibility of normal speech. This allows people to communicate efficiently across mountainous terrain, at sea, or in dense forest. It’s great for hunting because it sounds like birdsong, so doesn’t tend to scare off prey.

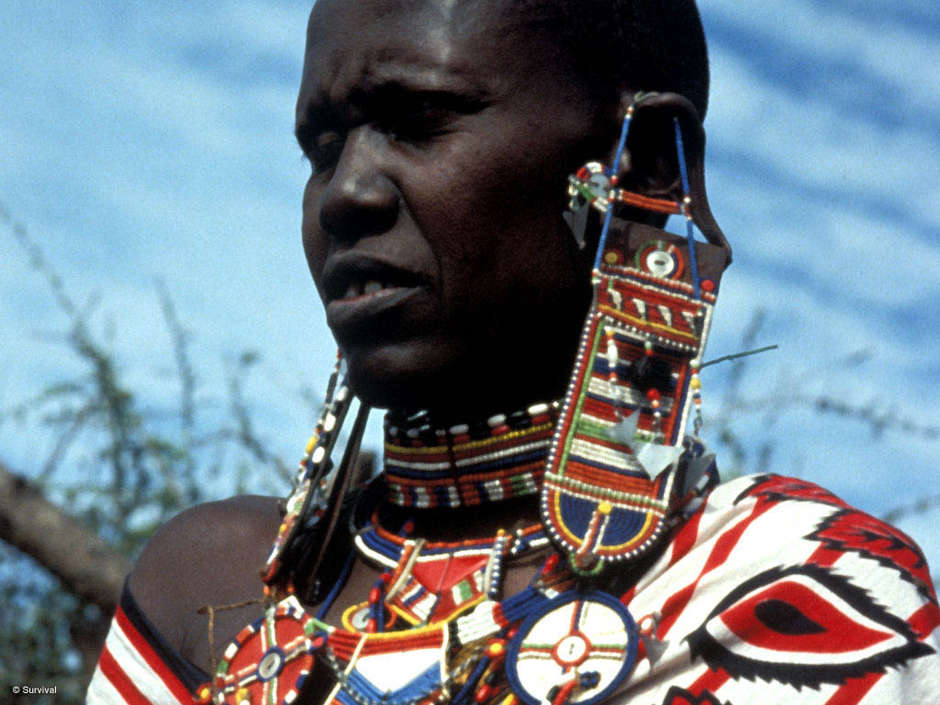

‘The © Survival International

The language you speak shapes how you relate to the world, but it does not limit what you are able to think and understand. While we would order a sequence of events or images from left to right, start at the left, end on the right, speakers of an Indigenous Australian language order events from east to west, like the course of the sun through the day. That means that the order in which they would put, say, a sequence of pictures showing a person aging, would change depending on the position they were facing. Most of us lack this ability to instinctively sense east and west, so we would be unable to put pictures in the ‘correct’ order according to speakers of that language. However, just because we see the world differently, doesn’t mean we don’t understand their logic.

Whatever language you speak, people are people. Words like ‘mama’ and ‘dada’ are remarkably similar in almost every language, including variants like ‘tata’, ‘papa’ and ‘nana’. Is this evidence of some kind of deep historical relationship between all languages? No. What it actually shows is that all babies’ mouths are made the same. Sounds like ‘ma’, ‘pa’, ‘da’, ‘ta’, and ‘ga’ are the easiest to make, so babies learn those first. All doting parents assume their child must be addressing them personally, so ‘mama’ and ‘dada’ become part of the vocabulary.

Language shows us that human beings are all fundamentally alike, yet at the same time, diverse, innovative and unique in fascinating ways. It not only reveals the dazzling variety of human culture and experience, but also gives unique insight into what it means to be human, and the limits and possibilities of our minds. Things we might assume to be universal to all humans, that the past is behind us and the future ahead of us, that what follows 1 is 2, that blue and green are different colors, turn out not to be the case for everyone; other languages do it differently. There is even evidence that the language you speak actually changes the structure of your brain. Already, it is estimated that "97 of human languages that have existed through our history are now extinct.":https://www.quora.com/How-many-dead-languages-are-there This represents a phenomenal gap in our knowledge and understanding of ourselves as human beings. When even a single language dies, a vital piece of the human puzzle is forever lost.

Wanniyala-Aetto children are now taught the language and religion of the dominant Sinhalese population. © Survival International

The fundamental cause of language death is when children no longer speak the language of their parents. This can happen for a number of reasons, but one key factor is when children are made to feel ashamed of speaking the language of their family. Survival is campaigning to stop the “reprogramming” of Indigenous children in Factory Schools around the world, where the dominant language and culture are imposed on Indigenous children.

Similar schools have existed in the histories of Australia, Canada and the US, where they are known as “residential schools”. As well as accelerating the extinction of hundreds of Indigenous languages, the trauma inflicted on victims and communities carries down the generations and is still inflicting suffering to this day. Join us now to support a model of education for Indigenous children that is rooted in the land, language, knowledge and beliefs of the community. Not only to give them a sound education but also to take pride in themselves and their people; for tribes, for nature, for all humanity.

‘A © Toby Nicholas/Survival

__________ More than 150 million men, women and children in over 60 countries live in tribal societies. Find out more about them, the struggles they face, and how you can help – sign up to our mailing list for occasional updates.

Languages die because people stop speaking them: due to social pressures, demographic change and external forces. Colonisation, and the globalised capitalism it subsequently spawned, has perhaps been the greatest murderer of languages in human history, and this legacy is alive and well in the present. Survival International is campaigning against Factory Schools, which actively contribute to language death by teaching tribal children not in their mother tongue, but only in the dominant dialect or the official language of the state. This systematic cultural erasure threatens the lives of millions of children, their families, Indigenous communities, and the survival of languages around the globe. Our campaign against Factory Schooling will launch later this year; sign up to our mailing list for updates.

There are around 7000 languages spoken on Earth, but 23 languages are spoken by around half of the world’s population. On the other hand, nearly 3000 languages are considered endangered, meaning that almost half of the planet’s current linguistic diversity is under threat.

The most linguistically diverse place on Earth is the island of New Guinea, which is split into the independent state of Papua New Guinea, and West Papua, which is under Indonesian occupation. In an area of 786,000 km², approximately 1000 languages are spoken. Compare this to Europe, where around 100 languages are spoken in an area of over ten million km².

There is a strong correlation between linguistic diversity and biodiversity; where there are most species of plants and animal, there are most languages spoken. Languages are closely connected to the environment they are spoken in, so in such areas they contain rich, detailed and technical knowledge about the flora, fauna, and habitat of that area. When a new species is “discovered” by scientists, you can bet your bottom dollar that the tribal people living in that area would already have had a name for that species and be highly knowledgeable about it. These languages are ecological encyclopedias, and, as they are for the most part unwritten, if they are no longer spoken, then this wisdom and understanding is lost to humanity forever. Biological diversity and linguistic diversity go hand in hand; if one is threatened, then so is the other.

Around half of all the world’s languages have no written form, but this certainly does not mean they are lacking in culture. Unwritten languages are rich in oral traditions; stories, songs, poetry, and ritual passed down through the generations that remain remarkably consistent and reliable through time. Scientists are finding more and more evidence for events that happened thousands of years ago which have been documented and preserved in Indigenous storytelling, re-told and impressively preserved over hundreds of generations.

No human being on Earth speaks a “primitive” language; there is simply no such thing. All languages have intricate and unique rules of sound, words and grammar that all the speakers of that language know and understand intuitively. In fact, Indigenous languages generally tend to be the most complex, specialised and idiosyncratic, especially those spoken in remote areas by only a few hundred people. Big global languages like English, Spanish or Mandarin Chinese are relatively simpler and on the whole follow more predictable patterns. Because of this uniqueness, the languages which are most at risk are arguably those that have the most to teach us about the incredible breadth and variety of human perception and experience.

Some Indigenous languages demonstrate that human speech is not limited to the spoken word. Most famous are perhaps the African drum languages, allowing messages to move between communities at 100 miles an hour. There are also around 70 languages that can be whistled. This isn’t like whistling the tune of a song, it means actually whistling in words and sentences with the flexibility of normal speech. This allows people to communicate efficiently across mountainous terrain, at sea, or in dense forest. It’s great for hunting because it sounds like birdsong, so doesn’t tend to scare off prey.

The language you speak shapes how you relate to the world, but it does not limit what you are able to think and understand. While we would order a sequence of events or images from left to right, start at the left, end on the right, speakers of an Indigenous Australian language order events from east to west, like the course of the sun through the day. That means that the order in which they would put, say, a sequence of pictures showing a person aging, would change depending on the position they were facing. Most of us lack this ability to instinctively sense east and west, so we would be unable to put pictures in the ‘correct’ order according to speakers of that language. However, just because we see the world differently, doesn’t mean we don’t understand their logic.

Whatever language you speak, people are people. Words like ‘mama’ and ‘dada’ are remarkably similar in almost every language, including variants like ‘tata’, ‘papa’ and ‘nana’. Is this evidence of some kind of deep historical relationship between all languages? No. What it actually shows is that all babies’ mouths are made the same. Sounds like ‘ma’, ‘pa’, ‘da’, ‘ta’, and ‘ga’ are the easiest to make, so babies learn those first. All doting parents assume their child must be addressing them personally, so ‘mama’ and ‘dada’ become part of the vocabulary.

Language shows us that human beings are all fundamentally alike, yet at the same time, diverse, innovative and unique in fascinating ways. It not only reveals the dazzling variety of human culture and experience, but also gives unique insight into what it means to be human, and the limits and possibilities of our minds. Things we might assume to be universal to all humans, that the past is behind us and the future ahead of us, that what follows 1 is 2, that blue and green are different colors, turn out not to be the case for everyone; other languages do it differently. There is even evidence that the language you speak actually changes the structure of your brain. Already, it is estimated that "97 of human languages that have existed through our history are now extinct.":https://www.quora.com/How-many-dead-languages-are-there This represents a phenomenal gap in our knowledge and understanding of ourselves as human beings. When even a single language dies, a vital piece of the human puzzle is forever lost.

The fundamental cause of language death is when children no longer speak the language of their parents. This can happen for a number of reasons, but one key factor is when children are made to feel ashamed of speaking the language of their family. Survival is campaigning to stop the “reprogramming” of Indigenous children in Factory Schools around the world, where the dominant language and culture are imposed on Indigenous children.

Similar schools have existed in the histories of Australia, Canada and the US, where they are known as “residential schools”. As well as accelerating the extinction of hundreds of Indigenous languages, the trauma inflicted on victims and communities carries down the generations and is still inflicting suffering to this day. Join us now to support a model of education for Indigenous children that is rooted in the land, language, knowledge and beliefs of the community. Not only to give them a sound education but also to take pride in themselves and their people; for tribes, for nature, for all humanity.

__________ More than 150 million men, women and children in over 60 countries live in tribal societies. Find out more about them, the struggles they face, and how you can help – sign up to our mailing list for occasional updates.